What Cops and Protesters Both Get Wrong: Police-Related Violence in New York City Has Been Falling F

- OurStudio

- Jan 6, 2015

- 5 min read

In 1972, an NYPD patrolman was executed at point-blank range after being lured by a fake call into an East Harle

m mosque. "I hope you die, you pigs," yelled members of an angry crowd, who threw bricks at the cops gathered outside in the aftermath. Next they lit a police car on fire.

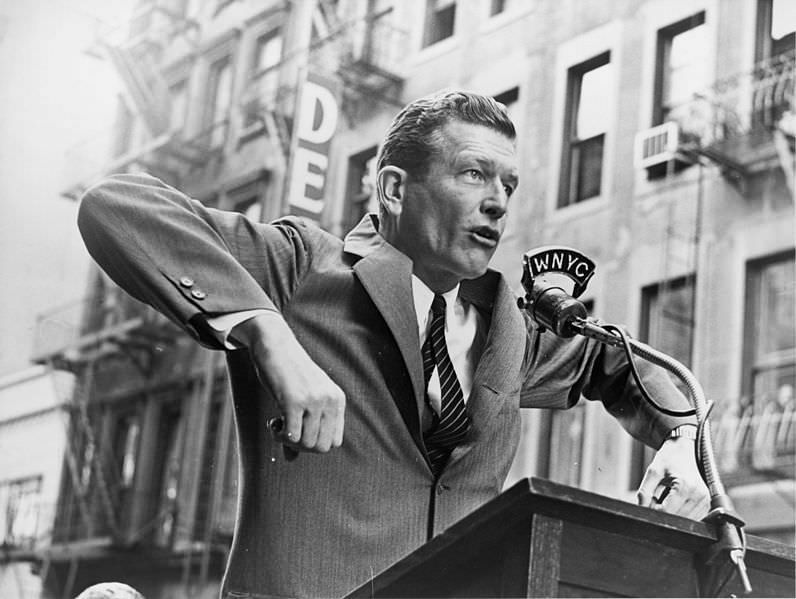

New York City Mayor John Lindsay refused to comment on the murder, telling the press that he was worried "what I say would sound like an attempt at justification of police action and the situation is too inflammatory in Harlem right now."

The rank and file was furious, and it's possible cops would have turned their backs on Lindsay at the fallen officer's funeral—as they did to Mayor Bill de Blasio more recently—but he wasn't at the funeral. He was in Utah skiing.

Today, cops and citizens say they're under siege like never before. At the recent demonstrations, protesters shouted slogans at cops, comparing the NYPD to the Ku Klux Klan and asking

Photographer/Mayoral Photography Office

how many kids they murdered that day. After the killing of two officers by a disturbed man inspired by the protests, a union leader claimed de Blasio had "blood on his hands" and instructed the rank and file to stop enforcing many laws as a way to preserve their own safety. For the second week in a row, the cops are listening.

Needless to say, we all want a world without tragic killings of any kind. But all the understandable outrage lacks context: For the past 44 years, rates of police violence against citizens, and citizen violence against police, have plummeted to a fraction of what they were in the bad old days. And when it comes to criminal justice reform, Gotham is in some ways a beacon compared to the rest of the country.

In 1971, NYPD officers shot and killed 93 people, which works out to 12 fatal shootings for every million residents. In 2013, by comparison, 8 people were fatally shot by the police, or one fatal shooting for every million residents—a decline of more than 90 percent. Also in 1971, 12 New York City cops were shot and killed—the same number as in all of the last fifteen years put together.

Also, police-related violence in New York isn't low just in relation to the city's historical rates; it's low compared to the rest of the country. Even if you accept the FBI's extreme undercount of fatal shootings by police nationally, citizens are significantly less likely to be shot and killed by cops in New York City than in the rest of the country.

Blaming the tragic killing of Officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu on the protesters or Mayor de Blasio is nonsense, and even today's most ardent critics of the NYPD condemned this senseless act of murder. But in the old days, there was a verifiable movement to kill New York cops.

The Black Panthers, the revolutionary nationalist group, once called on its members to shoot NYPD officers—and many listened. In May 1971, two cops were ambushed by men with machine guns on the Upper West Side. Two days later, two patrolmen were again ambushed and shot dead at a housing project in Harlem. In January 1973, two more cops were shot in their car, in an incident that bears many similarities to the recent execution of Officers Ramos and Liu. All of these incidents traced back to perpetrators with ties to the Panthers or the Black Liberation Army.

The recent spate of anti-police abuse protests were indirectly triggered by a profoundly disturbing video of a cop choking Eric Garner, a black-market cigarette seller who was resisting arrest and ended up dead. But what if there had there been ubiquitous surveillance and camera phones in decades past? A glance at the historical headlines conveys a sense of the horrors that might have been caught on video.

Take 1973: In January, an officer fatally shot an unarmed 16-year-old girl in Brooklyn because he claimed another woman nearby was pointing a shotgun at him. He faced no repercussions. In March, two white officers shot to death a plainclothes black cop who was in the midst of making an arrest. In April, an officer with a checkered history fatally shot a 10-year-old boy on the street in Brooklyn, who, according to some accounts, was unarmed.

Mayor Lindsay, who governed Gotham during the turbulent period of 1966 to 1973, had a relationship with the NYPD that makes de Blasio's almost seem warm and fuzzy by comparison. Frustration with Lindsay, in part, led cops to engage in a six-day strike in January of 1971, during which only 15 percent of the police force showed up for work.

By comparison, the NYPD's recent work slowdown is benign. (Another big reason for both actions: Gaining bargaining power in union contract negotiations.)

That's not to say that the protesters' complaints about the NYPD are groundless. Under de Blasio's predecessor, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, police-community tensions were exacerbated by the decision to send teams of inexperienced new recruits into minority neighborhoods to stop and frisk citizens on flimsy grounds. They routinely forced the men and women they apprehended to reveal small quantities of marijuana, and then arrested them—turning what would have been a mere fine for concealed cannabis into a criminal charge. But Mayor de Blasio and Commissioner William Bratton have laudably scaled back or ended these practices.

Here's the big picture: Over the past couple decades, the NYPD has significantly de-escalated the war on drugs. Prison sentences for drug crimes in New York have plummeted since 1992. Bucking the national trend, the overall incarceration rate has also fallen. As University of California criminologist Franklin Zimring found in his comprehensive statistical examination of policing and crime in the Big Apple, from 1990 through 2008, New York City saw a 70 percent decline in the number of black and Hispanic males aged 15-24 sentenced to prison. During the same period, the national rate shot up 65 percent.

Policing in New York works far better than it used to. And it's not about to revert back to the horrors of yesteryear.

There is also reason for optimism that the city's latest policing crisis will soon blow over as so many have

Source: The Brennan Center for Justice

before—not least of all because Mayor de Blasio had the good judgment to tap Bill Bratton, who proved himself a brilliant manager during his first stint as police commissioner by taming the NYPD's bureaucracy. There is nobody better positioned than Bratton to quell anger among the rank-and-file, and finish the job he started twenty years ago of turning the NYPD into a first-rate police force.

Comments