The Return of the Obamacare Death Spiral

- OurStudio

- Aug 17, 2016

- 7 min read

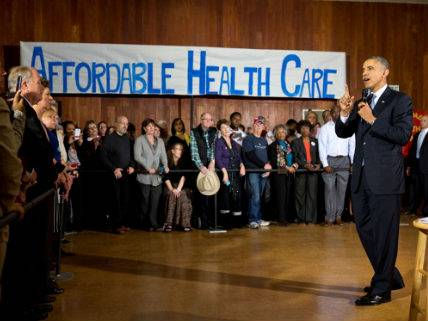

Whitehouse.gov

Earlier this week, Aetna, which covers about 900,000 people through the health exchanges created under Obamacare, announced that it would dramatically reduce its presence those exchanges. Instead of expanding into five new states this year, as the insurer had previously planned, the company said that it would drop out of 11 of the 15 states in which it currently sells under the law.

Aetna's decision follows similar moves from other insurers: UnitedHealth announced in April that it would cease selling plans on most exchanges. Shortly after, Humana pulled out of two states, Virginia and Alabama. More than a dozen of the nonprofit health insurance cooperatives set up under the law—health insurance carriers created using government-back loans in order to spur competition—have failed entirely. While some insurers are entering the exchanges, even more are leaving.

What this means is that in several states, and even more counties, there will be only one insurer available through Obamacare. In at least one county—Pinal County, Arizona—it is likely that there will be no insurer available on the exchange at all.

This slow exodus of insurers from the health law's marketplaces represents a serious threat to the continued stability and existence of its exchanges. Obamacare is perched on the edge of a death spiral.

The fundamental problem is simple: Insurers are losing money. Earlier this year, Aetna said it expected to lose about $300 million on the plans. UnitedHealth estimated losses on exchange plans in the range of $650 million. This is not a problem that is limited to big, profit-seeking insurance companies: The majority of the non-profit co-op plans created under the law have failed, citing an inability to pay claims using premium revenues.

This is simple business math. For insurers to operate on the exchanges, they have to bring in sufficient revenue to cover their claims. Some of them might be willing to accept losses up front on the promise of returns over time. But the losses can't go on forever.

And what the insurers who have left the program have made clear is that they believe that, absent changes, the losses will go on forever. "The vast majority of payers have experienced continued financial stress within their individual public exchange business," Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini said about the decision. In a call with investors last year, a representative from UnitedHealth said the company "saw no indication of anything actually improving" inside the exchanges. "We cannot sustain these losses," UnitedHealth CEO Stephen Hemsley said on that call. "We can't really subsidize a marketplace that doesn't appear at the moment to be sustaining itself."

Partisan defenders of the law have sometimes argued that Republicans in Congress crippled it by making it more difficult for the federal government to subsidize struggling insurers. At a minimum, they are overstating their case.

This is a reference to a provision inserted into a 2014 spending bill limiting the ability of the administration to dip into Treasury funds to pay out funds under the law's risk corridors provision. The risk corridors provision was essentially a backstop built into the health law to help insurers balance out profits and losses during the first years of the program. Insurers whose claims came in lower than expected would make payments into the government-run program, while those whose claims came in higher than expected would receive payments.

In theory, the payments even out, with some insurers paying in and others being paid out. That was certainly the expectation when the bill was passed: The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scored the provision as revenue neutral—costing taxpayers nothing.

But what would happen if claims from all the insurers came in higher than expected? The answer is that there was no plan for this possibility. In addition to the CBO's score, which while imperfect set expectations for the law, the Department of Health and Human Services did not provide for any source of funding should outgoing payments exceed collections.

So what Republicans did was to require the law to work as projected and as expected—and limit the administration's options to prop it up, at taxpayer expense, should things not go as planned.

As the cascade of insurance carriers exiting the Obamacare marketplaces makes clear, things are not going as planned.

In Aetna's case specifically, there is an additional complication: The company has proposed a merger with competing health insurance company Humana, but the Obama administration has blocked the move, with Aetna and the Department of Justice set to hash out the details on court later this year. In July, before the DoJ announced plans to oppose the merger, Aetna CEO Mark Berscolini sent a letter to the Obama administration stating that if the administration decided to block the merger, Aetna would respond by reducing its exchange business.

"If the deal were challenged and/or blocked," the letter, which was first published by The Huffington Post, says, "we would need to take immediate actions to mitigate public exchange and ACA small group losses," specifically by reducing the company's exchange presence to just 10 states. The letter suggests that a complete exit from the exchanges could be in the works if the merger is not allowed, saying that "it is very likely that we would need to leave the public exchange business entirely and plan for additional business efficiencies should our deal ultimately be blocked."

It's entirely reasonable to view Aetna's move, then, as the execution of a threat in a business negotiation with federal regulators. (It's also worth noting that the Department of Justice requested the letter from Aetna, which turned out to be a rather convenient document to have for making a public case against the insurer.)

At the same time, the core issue remains the same: Selling insurance on Obamacare's exchanges is not a good business proposition in many instances. Aetna was losing money in a way that was not, by itself, sustainable. Aetna was willing to incur losses on the exchanges—but only if allowed to expand its business in other ways. If Aetna was not incurring losses on Obamacare's exchanges, this would not be an issue.

And it is because of those losses that we are seeing what looks more than a little like the start of a health insurance death spiral in the exchanges. This is far from certain, and will depend in significant part on the results of the next open enrollment period, which starts later this year, as well as the decisions made by other health insurers under the law. But there are a number of warning signals to be watching.

We know what a health insurance death spiral looks like because we've seen them before, in states such as New York, New Jersey, and Washington. The experience in those states varied somewhat, but they all shared several essential qualities: The states put in place regulations requiring health insurers to sell to all comers (guaranteed issue), and strictly limiting the ways that insurance could be priced based on individual health history such as preexisting conditions (community rating). As a result, insurers ended up with large numbers of very sick customers who were very expensive to cover. Because they were subject to limits on how they could price health history, they responded by signficantly raising premiums for everyone. The new, higher premiums caused the healthiest, most price sensitive people to drop coverage entirely, which caused insurers to raise premiums further, resulting in yet more individuals dropping coverage, and so on and so forth, until all that remained was very small group of very sick, very expensive individuals.

Washington state's experience in the 1990s is particularly instructive: After the state put in place guaranteed issue and community rating rules, carriers saw an influx of unusually sick and expensive beneficiaries, as well as individuals gaming the system by signing up for coverage in advance of an expensive medical event, then cancelling as soon as that event was over. Insurers simply couldn't make money in the individual market, and so between 1993 and 1998, 17 of the state's 19 plans stopped selling individual insurance plans. The next year, the final two carriers left the individual market. It was a total meltdown.

The lesson most observers took from this was that insurance market regulations would not work without a mandate: In 1994, a Republican-led legislature had killed an individual requirement to carry coverage but left guaranteed issue and community rating in place.

Obamacare, of course, has a mandate, but what's happening in the health law's exchanges is starting to echo what happened in Washington and other states that experienced death spirals.

Individual insurance premiums have spiked all over the country. Far fewer people have signed up for coverage than expected, with sign-ups undershooting Congressional Budget Office estimates by about 40 percent. The people who have signed up, meanwhile, have tended to be sicker and more expensive to cover, according to health insurers. "For every dollar we brought in last year, we paid out $1.26 for medical care," Michael E. Frank, the president of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Montana, told The New York Times this week. "In the first six months of this year, we have already paid $4.17 million in medical costs for the top 10 individuals. That's $70,000 a month for those individuals."

And even with the mandate in place, some people appear to be gaming the system. A top actuary for insurer Highmark told the Times that in Pennsylvania, roughly 250 of its beneficiaries on had already incurred more than $100,000 in expenses this year. "People use insurance benefits and then discontinue paying for coverage once their individual health care needs have been temporarily met," he said, driving up the cost of coverage for everyone. Last year, UnitedHealth also indicated that individuals buying coverage and dropping it was driving losses.

As all this is happening, of course, insurers are bailing on the system, unable to make the numbers add up.

It's not an exact replica of the Washington state experience, but there are certainly similarities. The underlying point of all of this is that if the law's exchanges remain on their current wobbly trajectory, its dysfunction is nearly certain to grow. And the rough negotiations between Aetna and the administration may make insurers who are already losing money even more wary of further participation in the system.

That means that the prospect of significant further reforms may soon be on the table—which will likely include everything from poorly conceived state-based single-payer plans to poorly conceived federal health insurance systems to, ah, poorly conceived conservative reforms. If anything, reforming health reform will be even more difficult than the initial project.

In the meantime, Obamacare will likely continue to falter. The law, of course, has avoided multiple potential near-death expenses thus far, and it may still survive. But at the moment, at least, it looks like one sick patient.

Comments