The <em>New York Times'</em> Nail Salons Series Was Filled with Misquotes and Factual Errors. Here's

- OurStudio

- Oct 26, 2015

- 17 min read

A two-part seri

es in The New York Times on nail salons has brought sweeping changes to an industry dominated by Korean and Chinese immigrants. Written by reporter Sarah Maslin Nir, the series, which ran in print on May 10 and 11, focused on the plight of nail salon manicurists in New York City and Long Island. It depicted a community of immigrant workers paid shockingly low wages to beautify the fingers and toes of affluent New Yorkers while inhaling toxic fumes that cause miscarriages and cancer.

Nir, who spent 13 months on the project, said in an interview that she initially pitched the story as an "expose," adding that the "great lesson" readers should come away with is that there's "no such thing as a cheap luxury." The only way "you can have something decadent for a cheap price is by someone being exploited." (My Reason colleague, Elizabeth Nolan Brown, wrote a critique of Nir's series shortly after it was published.)

The "great lesson" here is actually something different. I've spent the last several weeks re-reporting aspects of Nir's story and interviewing her sources. Not only did Nir's coverage broadly mischaracterize the nail salon industry, several of the men and women she spoke with say she misquoted or misrepresented them. In some cases, she interviewed sources without translators despite their poor English skills. When her sources' testimonies ran counter to her narrative, she omitted them altogether.

The second article lent the Times' imprimatur to unproven theories, while committing science journalism's cardinal sin of highlighting alarmist anecdotes that aren't representative of systematic research.

If it hadn't had real-world consequences, the series—and subsequent attempt by Nir and her editors to parry criticism—wouldn't be worth such intense scrutiny. But the day after the first article appeared in the print edition of the Times, Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D-NY) announced a new multi-agency task force to inspect nail salons. In August, Cuomo issued an emergency order mandating that salons purchase a new form of insurance called a "wage bond" so that if owners are discovered paying their employees less than the legally required wage, the workers have recourse to collect.

The rush to legislate based solely on the Times' shoddy reporting has hurt the industry. New nail salons, "which used to open every week in New York," have stopped appearing, according to Aiming Feng, an accountant and leading business advisor to nail shops.

Salons once provided a steady source of jobs for undocumented immigrants; now many owners say they'll hire only legal workers who've completed an occupational licensing program because they're afraid of getting in trouble.

In September, two industry groups filed a discrimination lawsuit over the wage-bond mandate in New York State Supreme Court on the grounds that the state has unfairly singled out an Asian-dominated industry.

Another group has organized multiple protests, including a demonstration on October 6 in front of The New York Times Company's offices in midtown Manhattan. "Apology Now, Fire Nir!" was printed on one sign at the protest; "Shame On You New York Times, Your Lies Kill Our Shops," read another.

Another protest is scheduled at 11a.m. today in front of the Times building.

I'm not the first reporter to scrutinize Nir's reporting. In July, Richard Bernstein, a 24-year veteran of the Times who left the paper in 2006, published "What the Times Got Wrong About Nail Salons" in the online edition of The New York Review of Books. His knowledge of the industry comes through his wife, Zhongmei Li, who owns and manages two nail salons in Manhattan.

Bernstein charged that Nir's story focused on a small segment of the industry while ignoring the vast majority of nail salons, which pay above the minimum wage and hire only licensed manicurists. His piece specifically challenged the Times' claim that the Asian-language newspapers are "rife" with manicurist ads offering shockingly low wages. After Bernstein's story appeared, the Times' editors penned a public letter offering new evidence to support Nir's claim.

As I'll explain, the Times editors mistranslated and misconstrued that new evidence, which actually validates Bernstein's argument.

Nir and her editors declined my interview requests. Instead, a Times spokesperson provided a prepared statement, asserting that the paper is "extremely proud" of the series and pointing to the high number of labor violations discovered by Cuomo's inspection task force since the series appeared.

Those labor violations don't reveal what the Times claims they do. In its zeal to cite the government's ex post vindication of its own reporting, the paper further obfuscated what's really happening in the industry.

My look at Nir's reporting and its shortcomings will appear in three installments. First, I'll revisit the Times' back-and-forth with Bernstein and explain why the paper's claim that manicurists are paid shockingly low wages is based on shoddy research and misconstrued evidence.

Next, I'll look at Cuomo's inspection task force, the fines and violations being handed out to salon owners, and how the governor's actions have had the unintended consequence of making it harder for undocumented immigrants to get jobs in nail salons. (That article is now online here.)

The third installment will look at the Times' claim that chemicals present in nail salons are causing cancer and miscarriages, which is based on nonexistent evidence. (Click here to read part three.)

Job Ads "Paying So Little" They "Appear To Be a Typo"

In an early paragraph in the Times' first story in the nail salon series, we read:

Asian-language newspapers are rife with classified ads listing manicurist jobs paying so little the daily wage can at first glance appear to be a typo. Ads in Chinese in both Sing Tao Daily and World Journal for NYC Nail Spa, a second-story salon on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, advertised a starting wage of $10 a day. The rate was confirmed by several workers.

Richard Bernstein, who rightly called this paragraph a "linchpin" of Nir's first article, was incredulous that anyone would advertise a day wage of $10 given that his wife must guarantee wages of about ten times that to attract qualified applicants. So he went looking through the classifieds in back issues of the Chinese-language newspaper, The World Journal, and couldn't find a single ad that mentioned wages under $70 per day. He found one ad offering to pay between $110 and $130 pe

r day.

Other than the $10 ad that Nir references—which I'll return to in a moment—Nir doesn't cite any other specific ads paying wages so low they "appear to be a typo." But after Bernstein highlighted this passage in The New York Review of Books, Times editors Dean Baquet, Wendell Jamieson, and Michael Luo co-signed a letter defending Nir's reporting.

Their letter cites three more ads to support Nir's claim:

One [ad] from June 19, 2014, in the World Journal, for example, showed a starting wage of $40 a day for "small job"…Another ad from July 17, 2014 in The World Journal also showed a $40 a day wage. And another one from April 17, 2014 showed a pay range of $40 to $90 a day. These examples were taken from a random sampling of days.

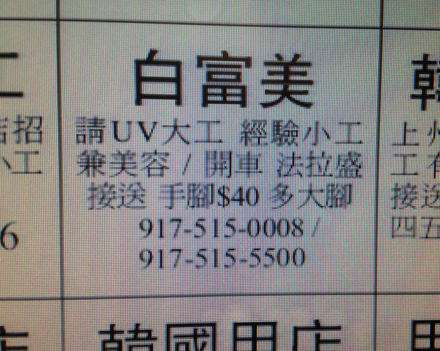

The Times editors also posted high-resolution copies of the three ads to the photo-sharing site Flickr, but, somewhat suspiciously, the Chinese characters are out of focus and my translator couldn't decipher them. So I went to The World Journal's headquarters in Queens and obtained new copies of the ads, which I've posted here.

The ads don't say what the Times editors claim they do. Two of the ads they cite actually say that a mani/pedi costs $40 at the salon, not that a worker would be paid $40. Why include such a detail in a job ad? It implies big tips.

The first one translates as: "UV gel, big jobs, experienced small jobs, and cosmeticians. Flushing pickup and drop-off. Mani/Pedi $40 with commission, good percentage tips, may file taxes."

The second one reads: "Seeking UV gel experienced big jobs, small jobs, and cosmeticians. Pickup and drop-off at Flushing, Mani/Pedi $40 or more, expensive jobs."

Both ads were posted by Michael Ling, the owner of a nail salon in Fairfield, Connecticut. (The World Journal is a regional paper). In an interview conducted through a translator, Ling confirmed that what the ad said is correct. He included the price of a mani/pedi to entice potential employees by indicating that the store serves a wealthy, and likely generous, clientele.

The third ad the Times editors produced in response to Bernstein offers a wage of "$40-90." I interviewed the salon owner who posted that ad, David Lee. His shop went out of business in 2014, in part, he says, because he struggled to attract enough qualified manicurists. Lee says he was offering full-time workers a base salary of $90 per day and part-time workers $40 per day.

The $10 Ad

The only remaining evidence that the Asian-language newspapers are "rife" with ads listing "jobs paying so little the daily wage can at first glance appear to be a typo" is the $10 ad Nir specifically referenced.

"[I]t's not clear whether the reporter saw the ad at all," Richard Bernstein wrote in the New York Review of Books.

It turns out Nir did see the ad, but once again it doesn't say what the Times claimed it does. The day Bernstein's article appeared, Nir posted an image of the ad to Twitter:

The ad that "doesn't exist" according to @R_Bernstein & @nybooks who calls me a liar & didn't bother to interview me pic.twitter.com/TH4SmWlo6r — Sarah Nir (@SarahMaslinNir) July 25, 2015

That ad (Nir later tweeted a magnified version) actually offers to pay manicurists $75 per day in base pay; under that, it notes that "apprentices," or "trainees," can earn $10 per day.

What does it mean to be a "trainee?" Was Nir wrong to leave that detail out?

"Lest there be confusion…these are not the equivalent of unpaid summer interns at a magazine," wrote the Times editors in their defense of Nir's reporting. "Interviews by Ms. Nir and her team with employees of the salon confirmed that these were essentially beginning workers, doing the same jobs as others in the salon," they wrote.

But the salon owner who posted the ad disputes the Times' characterization—as does one former apprentice who answered that $10 ad back in 2014.

"We would never let them touch customers," said Yun Jun Long, the former owner of NYC Nail Spa, in an interview conducted through a translator. "If the customer is spending money, you can't stick them with an inexperienced worker." (Long's salon went out of business a month after the Times' story appeared, which he attributes to the negative publicity. He's now helping to organize the recent protests.)

The $10, he says, was meant to cover subway fare and lunch, and those who signed on could come and go as they pleased. During slow periods they could practice on other employees or receive lessons from Long's wife and mother-in-law—partners in the business who also worked in the store.

At my request, Long put me in touch with Jay, a 28-year old undocumented immigrant and former trainee at NYC Nail Spa who asked that I not include his full name. Through a translator, Jay confirmed that he never worked on a customer for the two weeks when he was making just $10 per day.

Nir has said on Twitter that she visited NYC Nail Spa six times. (Long recalls seeing her come into the store just once.) Even if that's true, it wouldn't be surprising if she misreported what was actually going on in the shop; at several points in her coverage, Nir muddled what apprenticeship programs of this sort are all about.

The main character in the first installment of the series was a 20-year-old Chinese immigrant named Jing Ren, who also went through an apprenticeship program. Without any prior experience doing nails, she got a job working unpaid for her first three months. Ren was also initially asked to pay $100 to the owner of her salon for teaching her basic skills.

Times readers may find this practice reprehensible, but Nir left out background details that might lessen their outrage. These apprentice programs are an alternative to going through one of the New York State-certified nail training programs, where tuition is about $1,000 and students must complete 250 hours of formal training before getting licensed. It was technically illegal to work as a manicurist without completing one of these training programs when Nir was doing her reporting. (In July, two months after the Times series appeared, the state passed a bill creating a legal pathway to learn on the job, which I'll discuss in the next installment in this series.)

This type of arrangement is by no means an industry norm, but some salon owners flouted the law because they had more customers than employees; generally, the demand for skilled labor outpaces the number of licensed manicurists the beauty schools can mint. They got away with it because enforcement was lax.

Like Jay, Jing Ren had the option of spending about a month and a half studying at a state-certified school and paying $1,000 to learn her craft. Instead, she opted to pay $100 and work for no pay for three months. It's not clear that Nir ever asked Ren why she made that choice.

Jay, who was in debt when he started as a trainee at NYC Nail Spa, couldn't afford beauty school. The apprenticeship program worked out for him: Now he's employed as a manicurist at a salon in New Jersey, where his daily base pay is $90, not including tips.

The apprenticeship program also worked out for Jing Ren, who by the end of the Times story was making $65 a day in base compensation.

Are Apprenticeship Programs Prevalent in the Nail Industry?

Nir declares that "[Jing Ren's] deal was the same as it is for beginning manicurists in almost any salon in the New York area." (Italics mine.)

Yet she provides no proof for this statement, and all the available evidence indicates that Ren's deal was unusual. There are 30,610 licensed manicurists in New York State, all of whom would have had no need for an apprenticeship program. According to the Korean-American Nail Salon Association, there are more than 7,000 shops.

Nir supports this claim with anecdotal examples, including a disputed paragraph about a shop called May's Nail Salon, located on 14th Street:

Step into the prim confines of almost any salon and workers paid astonishingly low wages can be readily found. At May's…new employees must pay $100, then work unpaid for several weeks, before they are started at $30 or $40 a day, according to a worker. A man who identified himself as the owner, but would give his name only as Greg, said the salon did not charge employees for their jobs, but would not say how much they are paid.

The owner of May's Nail Salon is actually a woman named Bao Mei Fitzgibbons, who goes by "Mei." Greg, who Nir mistook as the owner, is an employee at the shop. Nir could easily have found Fitzgibbons' name by searching New York State's online corporation and business entity database.

Fitzgibbons says she was never interviewed by Nir, and scoffed when I asked if she charges new employees $100. "Think about it," Fitzgibbons says, "you work for me and I charge you $100?" The framed licenses of Fitzgibbons' employees are prominently displayed on the wall of her shop, indicating that they went through the official, state-authorized training program.

Fitzgibbons says she observed Nir come into her store and engage one of her manicurists in conversation without a translator. According to Fitzgibbons, the woman, who barely speaks English, later said that she was misquoted in the Times. The manicurist says she told Nir—again according to Fitzgibbons—that there are salons out there that charge trainees $100; she didn't say that May's is one of them.

(On my behalf, Fitzgibbons reached out to the manicurist interviewed by Nir, who no longer works at the store. Fitzgibbons says the woman declined my interview request on the grounds that "she doesn't want publicity.")

In another case, Nir spent time reporting at a salon that hires only licensed manicurists trained at a beauty school but left it out of her coverage.

ThinkPink is a small chain of nail salons in Manhattan run by Eun Hye Lee (she goes by "Grace"), who says she was interviewed by Nir. Lee, who is careful to maintain her books to the letter of the law, granted my request to inspect her payroll records. They showed that one experienced manicurist at ThinkPink's West Village branch had earned $680 in base pay, plus $216 in overtime, totaling $896 for a 48.5 hour week. A beginning manicurist in the same shop earned $493 for a 39-hour workweek, or $12.64 per hour.

Lee says Nir first interviewed her at ThinkPink in 2014. Several months later, she returned unannounced and asked for a pedicure. She struck up a conversation with her manicurist, a Chinese immigrant named Xiao Su, who goes by Zoey.

Lee put me in touch with Su, who no longer works at ThinkPink. She said in a phone interview that she told Nir that the pay at ThinkPink was "very good" and that Lee was a good boss who's always "very nice." She declined to tell Nir her salary, deeming it a rude question. Su, who emigrated from China in 1997, is a licensed technician who attended manicurists' school.

Neither ThinkPink, nor Nir's interview with Lee, were mentioned in the Times' coverage.

More Evidence of Low Wages?

To gauge the average pay for manicurists, Nir might have turned first to the federal government's Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The agency reported that in 2014, manicurists in New York's metropolitan area earned an average hourly wage of $9.19 per hour. It also reports an annual mean wage of $19,110.

BLS data, which is routinely cited in the Times, is subject to error and certainly overly precise. But in this case, these figures are the best information available. And the numbers indicate that the average manicurist earns above the minimum wage.

Instead of citing the BLS' numbers, however, Nir relied on her own survey that included "more than 100 workers." In fact, other than the classified ads, this is her main piece of evidence that the "vast majority" of salon workers earn less than the minimum wage.

Nir collected the data on the streets of Queens early in the morning, where salon owners (mostly from Long Island) often pick up manicurists in vans and drive them to work, and in chats that she struck up with manicurists (many of whom aren't native English speakers) while having her nails done.

In an interview with the Times about her series after it appeared, Nir says she kept "detailed spreadsheets" with this information. I asked for a copy of these spreadsheets. She declined my request.

Gathering data of this sort is inherently difficult, even for professionals. Pollsters at organizations like Gallup, Pew, and BLS strive to reach population samples that mirror the broader communities they're studying. They carefully frame questions in an unbiased manner, and only impartial interviewers do the asking. Under the best of circumstances, figures derived with these methods are imprecise and reporters generally cite them along with a margin of error.

Economists are skeptical of the wage survey data collected by the BLS because it's based on trust and memory. (How many hours did you work last week?) The gold standard in wage data—reported by the Bureau of Economic Analysis—is derived from documentation that companies are required to provide the government related to unemployment insurance.

The Times might have hired a polling firm to improve on the BLS' finding. Instead, it relied on Nir's survey, which was drawn from a non-representative sample and carried out by a reporter who won't share her methodology, question phrasing, or tabulated results. There's simply no reason to believe that Nir's data presents an accurate, representative picture of nail industry wages.

Also, Nir's report doesn't discuss gratuities. In fact, nowhere does the Times coverage attempt to gauge average daily tips in the industry or what workers actually take home in total compensation.

This is like writing a 7,000-word piece on what waiters make for a living but focusing only on base compensation. "There should have been several paragraphs on the subject," says Aiming Feng, the accountant and business consultant who counts about 50 nail salons as clients. (Feng also volunteers once a week at once a week at the Lin Sing Association, a social service organization in Manhattan's Chinatown, where he helps manicurists with legal and tax issues.)

Feng says that during "sandal season" at many shops tips equal or exceed base compensation.

Another "Damning" Piece of Evidence?

Nir offers more proof that the "vast majority" of manicurists earn less than the minimum wage: a two-sentence summary quote derived from an interview with Sangho Lee, the president of the Korean-American Nail Salon Association.

Nir writes:

[Lee] declined a request to address issues of underpayment. So many owners do not pay minimum wage, he said, that he believed answering any questions would hurt the industry.

In their letter defending Nir's reporting, the Times editors highlighted Lee's testimony as among "the most damning findings."

These two sentences came from the roughly two-and-a-half hours Nir spent interviewing Lee on two occasions. First, she met with him in person at the Association's office in Flushing, Queens with a Korean translator named Jiha Ham present. She later did a follow-up interview over the phone without a translator. According to Lee, Nir's paraphrase of his statement comes from the second interview.

Lee says that he was misquoted. "I told her that like any industry, there are nail salons that pay less and have worse conditions," he said. "Then I told her that even though 80 to 90 percent of the industry pays much more than the minimum wage, it would inappropriate for me to say anything negative about the industry as the president of the leading industry association."

Is Lee telling the truth that Nir distorted his comments? Since there were no third-party witnesses to the conversation, there's no way to know. But it's hard to believe that Lee would disparage the nail salon industry.

Founded 28 years ago, the Korean-American Nail Salon Association's mission is to promote best practices in the industry. It has 1,200 dues-paying member stores. A thick glossy magazine published annually by the Association includes letters from elected officials lauding nail salons for their contribution to the local economy. The group also awards an annual $1,000 scholarship to six college students whose parents work as manicurists in its members' shops.

So why would the president of an industry organization undo decades of hard public relations work by making a "damning" statement to a Times reporter? Maybe Nir misconstrued his remarks: Lee barely speaks English, and yet Nir interviewed him over the phone without a translator on the line.

How the Times Responded to a Salon Owner's Attempt to Correct the Record

Nir writes that at Iris Nails on Manhattan's Upper East Side "longtime workers described starting out at wages of $30 and $40 a day."

It's hard to believe that even beginning manicurists at Iris Nails would earn such meager pay. Located in one of New York City's wealthiest neighborhoods, Iris is the type of shop manicurists aspire to work at for the generous tips.

When reporting the story, Nir left a message for Iris Nails' owner, a Korean immigrant named Alex Park. He says he didn't return her message because he didn't understand the nature of the request.

When Park attempted to defend his reputation after the article appeared, the Times thwarted his efforts. The whole episode highlights the power imbalance between the Times and an immigrant community lacking in media savvy.

Park emphatically denies that his workers earn so little in base pay. He estimates that his lowest-level employees earn about $180 a day, including tips, and his most experienced employees can earn as much as $400 per day including tips and commission. (Park declined to allow me to examine his wage statements.)

After the article appeared, Park hired attorney Daniel Kim to contact the Times and demand a correction. Kim had a back and forth with the company's assistant general counsel, David McCraw. (Through a spokesperson, McGraw declined my request for an interview.) The paper refused to alter the online version of the article, and it didn't investigate the truthfulness of Park's claim. Instead, Kim says, McCraw agreed that the Times would print a letter to the editor written by Park.

Kim shared with me the letter Park submitted to Sue Mermelstein, an editor in the paper's letters department:

To the Editor: Your recent article "The High Price of Pretty Nails" will damage my business, Iris Nails. It seems that you needed a nail salon in a well-heeled neighborhood and targeted my business. I am preparing to retire after having worked for more than 22 years without any incident. Many of the employees in this type of services business have learned, earned and moved on to open their own shops. I have always treated all of my employees fairly and never took advantage of them. There is no employee who receives $30 to $40 a day on a full-time basis. There is no employee who receives below the minimum wages required by the State of New York. In fact, most of our employees make double of minimum wages including tips. Korean-American business owners in New York are very hard-working people. We have dedicated our lives to whichever field afforded us an opportunity to prosper and live out the American dream. I write this letter with great sorrow and anger.

The Times did print a version of the letter on May 17—but with notable changes.

First, it cut out Park's assertion that the paper had erred in its reporting. These three sentences were dropped:

There is no employee who receives $30 to $40 a day on a full-time basis. There is no employee who receives below the minimum wages required by the State of New York. In fact, most of our employees make double of minimum wages including tips.

In their place, the Times added a new sentence that reads, "I am committed to abiding by the law in paying my employees." In other words, the rewrite makes it sound as if Park was conceding that the Times' reporting on his store was not only correct, but that it inspired him to reform his illegal practices.

Times editor Sue Mermelstein said in a phone interview that there was an extensive back-and-forth with attorney McGraw over the wording of the letter. "We don't have the resources to go out and check the facts," she says, "and we didn't want to let him make a statement that we felt was inaccurate."

So they decided to cut out Park's contention that the coverage was inaccurate and replaced it with a line that McGraw "felt comfortable with because it's not a factual statement."

The Times ran the new wording by Kim and Park, and they signed off on it.

Attorney Kim doesn't recall the specific details, but says his client decided not to pursue the matter any further because he's "afraid of The New York Times."

Did the Times Get the Story Right Anyway?

Nir's claim that manicurists earn shockingly low wages was based on mistranslated and misconstrued classified ads, anecdotes and interviews contested by her sources, and an anecdotal survey that she used in place of official data published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Yet did she still get the story right? In response to Nir's critics, the Times has pointed to the high number of minimum wage violations reported by the state Department of Labor since the article appeared.

In the next piece in this series, I'll scrutinize those violations and explain why, in fact, they don't show what the Times claims. (That article is now online here.)

Comments