Silicon Valley May Rue the Day it Called for Government Intervention Against Microsoft

- OurStudio

- Dec 26, 2018

- 5 min read

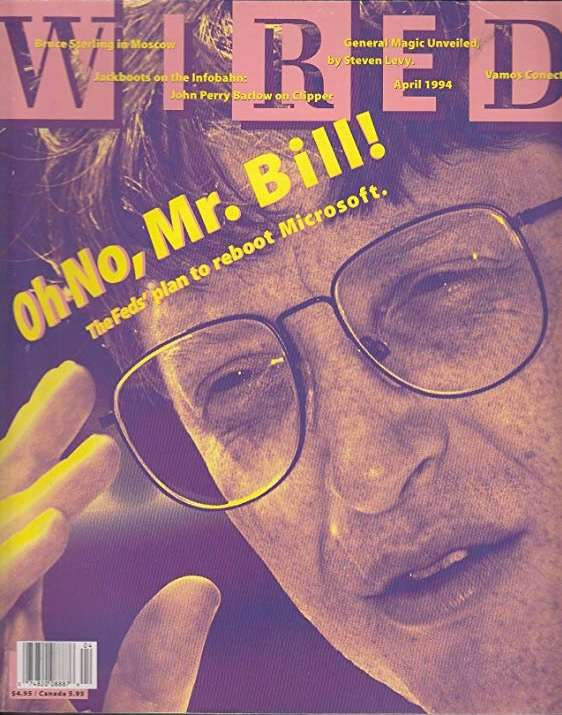

Wired, 1994

In a new Cato Policy Report, tech analyst Drew Clark lays out the ways in which government regulation often bites the ass that got it started in the first place. He notes that for much of the past several decades, "Silicon Valley"—that rough descriptor of tech and internet-based companies—was both the poster child for dynamic, forward-looking American capitalism, and largely unregulated by the federal government, especially compared to more traditional industries.

But all good things have got to end, and Clark documents how Washington started to take an interest in West Coast tech. Ironically, it was Silicon Valley who came a-calling first, "in the 1990s with the antitrust case against Microsoft, and again more recently in the battle with internet service providers over net neutrality." In each case, he notes, the alarm was sounded by other tech sector people and now, "they entangled the federal government in their industry in ways that are coming back to haunt them."

Clark writes that "net neutrality" rules were aimed at telecom firms (especially cable companies providing internet access) and promulgated and pushed by online bandwidth hogs including Netflix, Google, eBay, and Amazon. It was all good to start regulating the internet as long as it was the pipes being regulated and not what flowed through them (indeed, the rallying cry of net neutrality was that all data should be treated equally!). But that's not the way it played out. The Open Internet Order of 2015 has been rescinded (that's a good thing, incidentally) and now Washington is far more concerned with what's being transmitted rather than what ISP is transmitting it or at what speed it's being sent:

Silicon Valley's regulations-for-thee-but-not-for-me attitude has come back to bite them. They want the strictest form of regulation for telecommunications providers but no scrutiny of themselves, and now the tables have been turned. [Federal Communications Chairman Ajit] Pai has not hesitated to point out the hypocrisy as he has moved to undo the net neutrality rules. In a November 29 speech in the lead-up to his net neutrality rollback, he said that the tech giants are "part of the problem" of viewpoint discrimination. "Indeed, despite all the talk about the fear that broadband providers could decide what internet content consumers can see, recent experience shows that so-called edge providers are in fact deciding what content they see. These providers routinely block or discriminate against content they don't like." As examples, Pai cited Twitter's blocking Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) from advertising her Senate campaign with a message about partial-birth abortion, Apple's blocking an app for cigar aficionados, Google–YouTube's demonetizing videos from conservative commentator Dennis Prager and his "Prager University," plus "algorithms that decide what content you see (or don't), but aren't disclosed themselves" and "online platforms secretly editing certain users' comments." Others have termed the need for clarity about algorithms as a form of "search neutrality." The next day, for good measure, Pai blasted Facebook and Twitter for contributing to the rise of incivility in public discourse and "the breakdown in human interaction."

Pai is good on free speech and business freedom generally, so I wouldn't worry too much about the FCC going after tech. But many members of Congress, from both sides of the aisle, are spending a lot of time grilling the leaders of Google, Facebook, and Twitter about why their favorite personalities or preferred candidates don't seem to be as popular as the congressfolks think they should be.

In just the few short years since net neutrality went from being a concept to a policy to a repealed policy, the public debate has shifted tremendously. Especially in a world that is dominated by limitless mobile internet (which will be accelerated by the rollout of 5G networks), questions about an ISP such as Comcast controlling the "last mile" of access are irrelevant; the number of fixed and mobile connections continues to grow along with the speed of those connections. Nowadays, everyone is fixated on whether this or that point of view is being shadow-banned, squelched, or even completely deplatformed. Writes Clark:

If regulation returns, the tables have turned such that Google and Facebook would likely be subject to any such rules that get passed. As AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson argued in a full-page advertisement in January, legislation "would provide consistent rules of the road for all internet companies across all websites, content, devices and applications." In other words, no more free ride for tech companies at the expense of the telecom players: neutrality regulation either applies to everyone or to no one.

And then there's antitrust, arguably a bigger deal if only because the remedies—including the breaking up of firms—potentially have much greater impact on a given company. Clark recalls

Eric Schmidt, who would later become CEO of Google, played a crucial role in rallying Silicon Valley against Microsoft through his role as chief technology officer at Sun Microsystems, and then as CEO of networking company Novell. Apple also played a role. The Clinton Justice Department put forward a theory about how Microsoft improperly leveraged the monopoly it had earned in the market for computer operating systems into the market for so-called middleware software. Hence, Microsoft was the original example of a "platform monopoly."

These days, it's Google (or its parent company Alphabet) that's most likely to spend a decade in court. Google controls something like 90 percent of online search globally and managed to slip the legal noose in 2013 when a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ruling found that the company "provided more benefits than harms to competition." But what goes around comes around, right?

That FTC decision not to sue Google is increasingly under fire, by conservatives as well as progressives. In late August, Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT) asked that FTC Chair Joseph Simmons revisit Google's role in search and digital advertising. That request came after three days in which Trump went on the warpath against Google, and also Facebook and Amazon, saying that the companies may be in a "very antitrust situation."

And Clark notes that even as Google has successfully argued in U.S. jurisdictions that no online company is a "natural monopoly," European courts have ruled differently and started handing out big penalties and tightening regulation.

Silicon Valley should take all this activity as a teachable moment. When the companies first went to the government in the 1990s to seek intervention against Microsoft, and when they pushed for FCC net neutrality rules more recently, they set a precedent that brought Washington into their industry. They took it for granted that regulators would never go after content platforms like their own, but now it is precisely those platforms that are squarely in the sights of many politicians.

Drew Clark's "Seeking Intervention Backfired on Silicon Valley" is a great resource about how calls to regulate Silicon Valley both originated within the tech sector and have come around now to hound some of the very people and firms who first called out the dogs. If there's one dimension it doesn't address, it's the public-choice economics angle, which would suggest that, similar to the railroads and other "trusts" back in the day, big businesses are often complicit in their own regulation. That is certainly part of what's going on today regarding Silicon Valley, where leaders of Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Apple (at the very least) have talked openly about the "inevitable" need for regulation while also happily volunteering to help legislators write it.

It's tough to stay at the top of your pyramid, after all, and most of the so-called FAANG companies (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google) are getting a little long in the tooth. Why not sue for peace and get on with your early retirement as a philanthropist or wise man of the world? A little regulation that helps to lock in your current market position can make that even easier.

Comments