Report: Imprisoning Drug Users Doesn't Stop Drug Use or Prevent Overdoses

- OurStudio

- Mar 8, 2018

- 3 min read

Louisiana imprisons people at a higher rate for drug crimes than any other state in the country. Oklahoma ranks second.

One might then think that Louisiana and Oklahoma would have correspondingly lower rates of drug use and drug overdoses. Nope. According to a new report released by the Pew Charitable Trusts, the two states rank pretty high in drug use and overdose deaths.

This newly released set of findings shows that incarcerating people for drug crimes does not correlate with either less drug use or fewer overdoses. Louisiana ranks 13th in the county in drug use. Oklahoma ranks 10th in rates of both drug use and overdose deaths.

Contrast them with permissive California, which ranks 47th in drug imprisonment (though keep in mind that still works out to nearly 16,000 people). California does rank very high in drug use rates. It's second, just behind Colorado—and this is excluding marijuana, which has been legalized in both states. But California also ranks 40th in drug overdoses, surprisingly low. So California may be more permissive and have greater drug use rates, but these drug users are less likely to die of overdoses than those in Oklahoma or Louisiana.

In short, years and years of incarceration-focused drug wars have done nothing to control drug use. Tennessee ranks fifth in prison sentences for drug use, while New Jersey ranks 45th. Yet they both rank nearly the same (40th and 42nd) in rates of drug use.

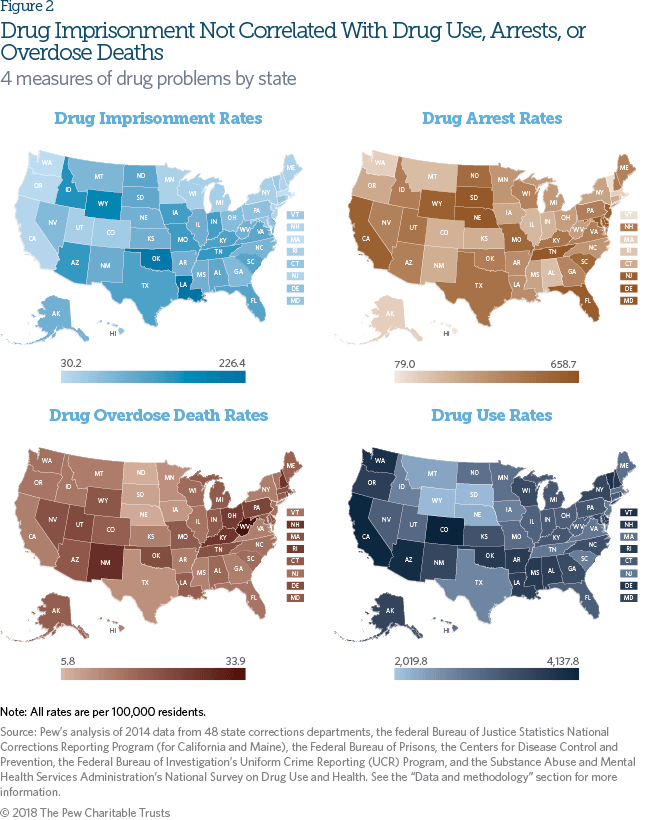

Pew even includes what is a nearly incomprehsible quartet of maps, entirely to highlight how impossible it is to determine any pattern between incarceration, arrests, drug use rates, and overdose death rates. Take a look (and perhaps scratch your head):

Pew

Pew sent these findings last summer to President Donald Trump's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. Making more of the report available right now is useful, given that the president has been playing up punitive responses to drug trafficking (though at this point I'd argue "punitive" is a euphemism when talking about a man who fantasizes about executing dealers). Trump is nominating a man to the U.S. Sentencing Commission who is opposed to reducing mandatory minimum sentences and insists that incarcerating more people leads to less crime. That, Pew reports, is not what the evidence shows:

The absence of any relationship between states' rates of drug imprisonment and drug problems suggests that expanding imprisonment is not likely to be an effective national drug control and prevention strategy. The state-level analysis reaffirms the findings of previous research demonstrating that imprisonment rates have scant association with the nature and extent of the harm arising from illicit drug use. For example, a 2014 National Research Council report found that mandatory minimum sentences for drug and other offenders "have few, if any, deterrent effects." The finding was based, in part, on decades of observation that when street-level drug dealers are apprehended and incarcerated they are quickly and easily replaced. On the other hand, reduced prison terms for certain federal drug offenders have not led to higher recidivism rates. In 2007, the Sentencing Commission retroactively cut the sentences of thousands of crack cocaine offenders, and a seven-year follow-up study found no increase in recidivism among offenders whose sentences were shortened compared with those whose were not. In 2010, Congress followed the commission's actions with a broader statutory decrease in penalties for crack cocaine offenders.

The report notes that, in defiance of everything coming from Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions, Americans by wide margins oppose lengthy mandatory minimum sentences as a tool to fight drug use and believe imprisonment for nonviolent offenders should be scaled back. Pew has polls from Maryland, Utah, and—yes—Oklahoma and Louisiana to back this up.

The report concludes:

Putting more drug-law violators behind bars for longer periods of time has generated enormous costs for taxpayers, but it has not yielded a convincing public safety return on those investments. Instead, more imprisonment for drug offenders has meant limited funds are siphoned away from programs, practices, and policies that have been proved to reduce drug use and crime.

Read the full report here.

For anybody who happens to be at South by Southwest in Austin on Monday, I'll be moderating a panel on state-level criminal justice reforms with representatives from some of the top organizations pushing for changes. Read more about it here, and come stop by.

Comments