Public Health Nannies Want to Stop You From Boozing. Why? Because Cancer

- OurStudio

- Nov 9, 2017

- 4 min read

Syda Productions/Dreamstime

The great thing about modern epidemiology is that you can find multiple studies to justify just about any public health policy you happen to favor. If you have a bias, there is plenty of confirming evidence from which to cherry pick.

Now come the doyens of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) with their statement on alcohol and cancer. ASCO cites research estimating "3.5 percent of all cancer deaths are attributable to drinking alcohol" in the United States. That would mean some 21,000 of the 596,000 Americans who died of cancer in 2016 were killed by cancers associated with alcohol consumption. In comparison, smoking tobacco is estimated to cause 32 percent of all cancer deaths (about 120,000 deaths).

Drinking booze is specifically associated with oropharyngeal and larynx cancer, esophageal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, and colon cancer.

The group treats consuming alcohol as a pure public health problem to which the only solutions are various forms of prohibition. They recommend regulating alcohol outlet density; increasing alcohol taxes and prices; maintaining limits on days and hours of sale; enhancing enforcement of laws prohibiting sales to minors; restricting youth exposure to advertising of alcoholic beverages; and resisting further privatization of retail alcohol sales in communities with current government control.

ASCO tells only part of the story about the health effects of drinking beer, wine, and spirits. There appear to be plenty of studies that find hard drinking increases an individual's risk of cancer. But the devil is in the cherry picking.

Lots of research finds light to moderate drinking involves a trade-off between a slightly higher risk of cancer and significantly lower risk of cardiovascular disease. Of course, the folks at ASCO are aware of this issue. In an attempt to deal with it, the ASCO statement cites a line of research that argues that "the benefit of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular health likely has been overstated."

For example, one 2005 study referenced by ASCO warned that due to confounding effects, "nonrandomized studies about the health effects of moderate drinking should be interpreted with caution." As far as I can tell, the ASCO statement itself cites meta-analyses of mostly nonrandomized studies in support of its claims that drinking alcohol causes cancer. Gander, meet sauce.

Claims for the cardiovascular benefits of moderate alcohol consumption remain somewhat controversial. That being said, a huge new meta-analysis in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC) probing the relationship of alcohol consumption to all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer-related mortality in U.S. adults finds significant health benefits from light to moderate drinking. To some extent there is a trade-off between reduced cardiovascular risks and higher cancer risks.

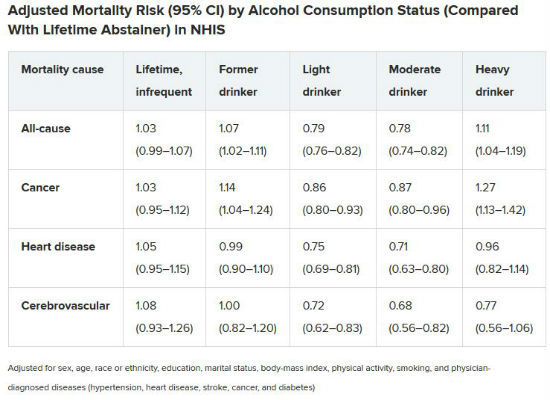

The JACC researchers subdivided drinkers into six groups: lifetime abstainers, lifetime infrequent drinkers, former drinkers, and light drinkers (fewer than 3 drinks per week), moderate drinkers (more than 3 and less than 14 drinks per week for men and less than 7 for women), or heavy drinkers (more than 14 per week for men and more than7 for women). Binge drinking was defined as five or more drinks on one or more days per week.

ASCO asserted that "even modest use of alcohol may increase cancer risk." However, Medscape reports of the JACC study that "light and moderate alcohol intake predicted reduced all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortalities in both men and women." That's right, light to moderate drinkers not only had lower risks of dying from any cause or from cardiovascular diseases, but also lower risks of dying from cancer.

On the other hand, the JACC researchers found "the highest levels of alcohol intake were associated with increased all-cause and cancer mortality in men but not women." Interestingly, even heavy drinkers had a lower risk of dying from cardiovascular diseases than did abstainers, infrequent, and former drinkers.

Medscape

There are other trade-offs not considered by the ASCO authors. For example, a new study using 13 years of wage and drinking data from the 1997 cohort of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth finds that drinkers tend to attain more education and to earn more than do abstainers. Researchers found by the end of the 13-year period wages of drinkers were, on average, 40 percent higher than those of abstainers (about $18 per hour as compared to $13 per hour). In addition, the researchers found that binge drinkers on average earned more than non-binge drinkers. They speculate that binge drinkers spend less overall time drinking and therefore are a bit more productive than folks who tipple on a regular basis.

This new research bolsters the findings of the Reason Foundation's 2006 No Booze? You May Lose policy brief. That report cited data suggesting that "drinking leads to higher earnings by increasing social capital." Folks who drink with colleagues and clients create wider social networks that provide them with greater opportunities to earn more. According to the report, "self-reported drinkers earn 10-14 percent more than abstainers."

The ASCO statement does not recognize either the health or income trade-offs folks who choose to drink may want to make. Even more importantly, the ASCO researchers fail to acknowledge that some people are willing to make the trade-off between the pleasures of imbibing beer, wine, and spirits and possible health consequences.

Of course, excessive alcohol consumption is a real problem for some people causing harm to themselves, their families and their friends. The ASCO oncologists certainly have a role to telling us their best guesses with regard to the risks they think we may run from our consumption of alcohol.

The ASCO authors' role, however, should be limited to informing us of the risks of boozing and then let us make our own decisions with respect the trade-offs involved.

Disclosure: On occasion, I have been known to consume more than 5 alcoholic beverages at one sitting.

Comments