Pennsylvania Subsidized <em>Creed II</em> With $16 Million in Tax Breaks, Even Though It Mostly Take

- OurStudio

- Nov 28, 2018

- 4 min read

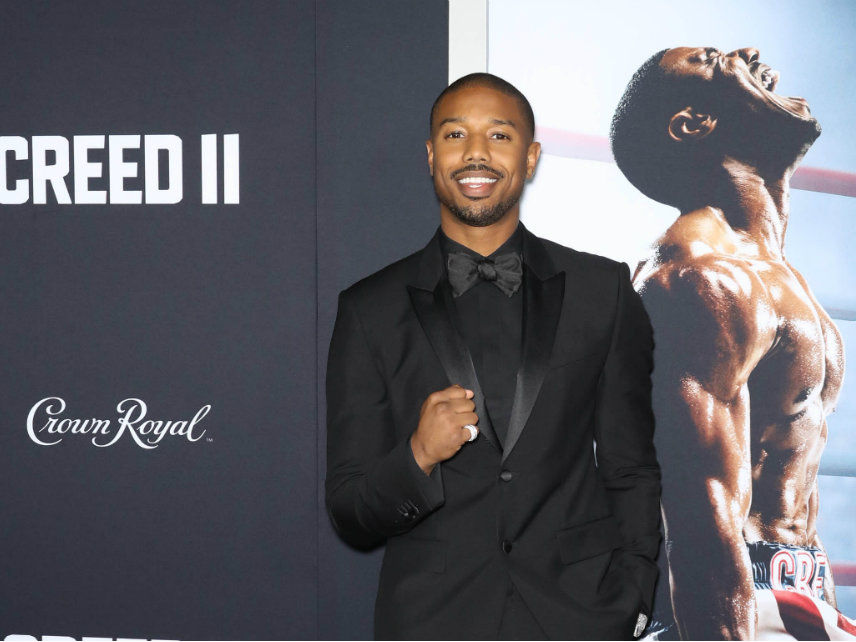

John Nacion/starmaxinc.com/Newscom

Pennsylvania taxpayers helped subsidize the filming of Creed II with $16 million in tax credits, despite the fact that the movie relocates its main characters (and perhaps the future of the long-running, iconic Rocky series) from Philadelphia to Los Angeles.

It's an apt metaphor for film tax credit programs in general—which are sold as a way to create local jobs in the movie business or as a way to get a state's top tourist destinations featured on the big screen—but mostly end up benefitting Hollywood production companies.

Creed II, released earlier this month, is the sequel to 2015's Creed, a spin-off of the Rocky series that sees a now-aged Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone) training up-and-coming boxer Adonis Creed (Michael B. Jordan). Adonis is, of course, the son of Apollo Creed, the antagonist from the first two Rocky films who later becomes a close friend of Rocky's before being killed in Rocky IV. The second Creed film pits Adonis against the son of Ivan Drago, the Russian heavyweight who killed his father—yeah, there's a lot of father-son stuff happening.

Those who watched the first Creed may recall that Adonis hailed from Los Angeles. He relocated to Philadelphia to train with Balboa and to find love—and, let's be honest, so the movie could feature yet another training montage featuring Philadelphia icons like the art museum steps made famous by the series' original entry.

This time around (minor spoilers follow), Adonis and his Philadelphia-born fiance Bianca Taylor (Tessa Thompson) decide to return to the West Coast. After a few early scenes in and around Philadelphia, much of the the rest of the movie in set in California (except for some scenes set in eastern Europe). Creed and Taylor have a luxury L.A. apartment, the mandatory training montage takes place in the middle of the California desert, and even Rocky himself is eventually convinced to decamp from Philly to L.A.

The move makes sense, for the story. "He came to Philly with a purpose, and sought out Rocky, and while we were mindful of that tradition of making Philadelphia a character in the films, we also wanted to do justice to Adonis by making the story follow his true path as well," Jordan told The Philadelphia Inquirer earlier this month. But as a $16 million ad for Pennsylvania, it fails.

If Pennsylvanians aren't unhappy about the decision to take Rocky out of Philly, maybe they should be unhappy about having to help pay for it. As the Inquirer's Laura McCrystal explains, Creed II got more than $16 million in tax breaks because the film met the requirement of having at least 60 percent of it's production costs incurred in Pennsylvania. That's really the only requirement, and it doesn't mean that 60 percent of the movie has to be set in Pennsylvania—the tax credit functions as a 25 percent rebate on practically any expense connected to filming in Pennsylvania, from catering lunch for production crews to buying camera equipment.

Pennsylvania hands out $60 million in tax credits each year to lure movie and television productions to the Keystone State. Some state lawmakers are pushing to remove that annual cap, McCrystal reports, so the state could soon be giving away even more.

Since creating the tax credit program under Gov. Ed Rendell in 2004, Pennsylvania has subsidized films that turned into major hits (Silver Linings Playbook got $4.4 million) and laughable flops (After Earth, Will Smith's disaster that was supposed to launch his son's career, got more than $20.4 million). The list includes critically-acclaimed films (Foxcatcher, a 2015 Oscar nominee, got $5.4 million) and movies that you'd only see if someone was paying you to do it (like M. Night Shyamalan's The Last Airbender, a movie probably best remembered for the controversy surrounding Shyamalan's decision to cast white actors as Japanese characters, which got $36 million in tax credits from the state).

Lots of states have similar programs, of course, but the incentives are basic crony capitalism with little economic benefit.

A 2016 study published in the American Review of Public Administration concluded that neither transferrable nor refundable film tax credit programs "affected gross state product or motion picture industry concentration. Incentive spending also had no influence." In Virginia, a 2017 state legislative study found that film tax credits had "a negligible benefit to the Virginia economy" and returned about 20 cents on the dollar.

"The film industry claims that they create jobs for local residents, but the most serious study of this issue found that out-of-state specialists—actors, writers, cinematographers, and so on—reap a disproportionate share of the benefits," wrote Robert Tannenwald, a professor of economics at Brandeis University, in a 2011 report for Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, a progressive think tank where he was a senior fellow at the time. "Residents get relatively low-paying jobs that disappear once a shoot is finished and the producer leaves town."

Like Adonis Creed returning to L.A., most of the money from Pennsylvania's film tax credit program also ends up out of state. In an exhaustive report published in 2016, Pittsburgh-based watchdog Public Source found that 99 percent of all film tax credits end up being transferred to "companies that have nothing to do with film or TV," essentially turning the film tax credit into "a backdoor tax break for some of the largest corporations and utilities operating in Pennsylvania."

In 2014, Pennsylvania's auditor general dinged the state agency that oversees the film tax credit program for not having clear metrics for evaluating the program's cost effectiveness, noting that the agency could not provide "evidence that metrics even exist."

But even by those low standards, making your residents subsidize a movie about a character who gets rich and successful in Philadelphia and then decides to move away seems to send an interesting message. Don't blame Adonis Creed for Pennsylvania's declining population and the decreased political clout that comes with it. Blame the people running the state who still think film tax credits are a worthwhile use of public resources.

Comments