L.A. Officials Use Olympics as Cover to Spend $26 Billion on Transit Projects That Have Little to Do

- OurStudio

- Mar 1, 2019

- 5 min read

Kc Click Click Media/Dreamstime.com

Los Angeles won't host the Olympics until 2028, but the area's transit agency, Metro, is already kicking things into high gear with an audacious "28 by 28" plan of building 28 major transit projects by the time international athletes and visitors start pouring into the city.

A lot of cities screw themselves over by building expensive infrastructure that will be used once for the Olympics and then left to rot (see Athens 2008 or Rio de Janiero in 2016). L.A.'s transit officials are studiously avoiding this mistake. Instead, they're making a much different mistake: using the Olympic games as a pretext to accelerate projects that have little do with the games and will cost billions more to finish in time for the opening ceremonies.

"This is about building transportation projects, regardless of whether there is a link to the Olympics," says Baruch Feigenbaum, a transportation expert with the Reason Foundation (which publishes this website). Framing these projects around the Olympics, he says, is a way of "selling the politicians and the voters on the need to get new funding."

Metro's "28 by 28" plan—first proposed in late 2017 and officially adopted by Metro last year—calls for $42 billion in new capital projects. It includes 13 rail transit extensions, five Bus Rapid Transit lines, seven road projects (including new highway capacity, tolled expressways, and interchange improvements), and a couple bike trails for good measure.

"Winning the 2028 Olympic Games gives us the chance to re-imagine Los Angeles, and ask ourselves what legacy we will create for generations to come," said Los Angeles mayor and Metro Board chairman Eric Garcetti when the plan was first announced. "This initiative is our opportunity to harness the unifying power of the Olympic Movement to transform our transportation future."

Notably missing from Garcetti's flowery language is any mention of facilitating travel to and from the Olympic events themselves. The reason for that becomes clear when you compare where these 28 by 28 projects are intended to go with where the events will actually be held.

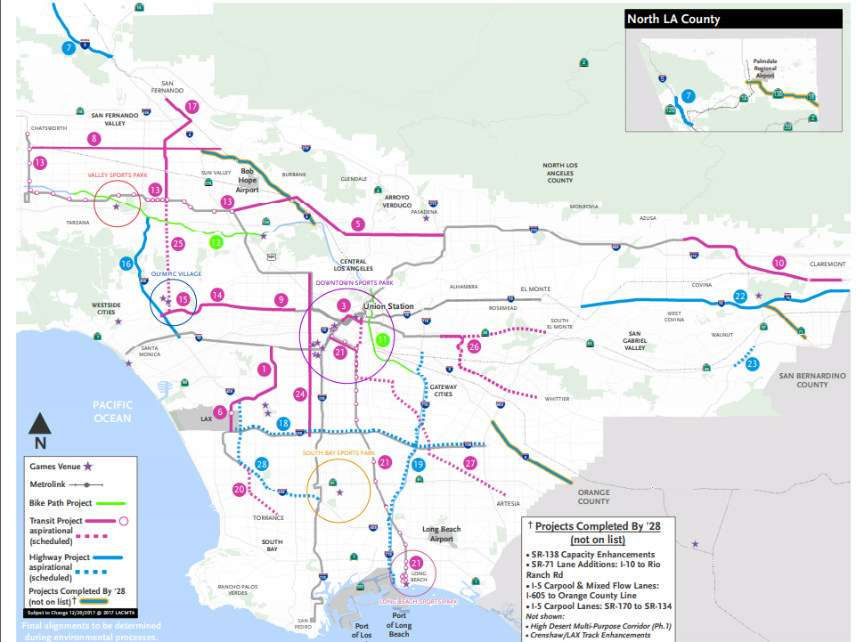

Metro

The Olympic Games themselves are largely supposed to be held in stadiums and sports facilities in downtown Los Angeles, save for a few aquatic and beach events in Santa Monica and Long Beach. These 28 by 28 projects \ are spread all across the vast Los Angeles County, with most coming nowhere near the planned Olympic venues. (See the map to the right.)

That's particularly true of the eight projects that Metro wants to "accelerate" to make them ready for the beginning of the games. The majority of projects in the 28 by 28 plan were already slated to be completed by 2028, leaving four rail and four roadway projects whose delivery schedule needs to be stepped up.

Expediting these projects is expensive, however. Very expensive. To get them done in time for the games, Metro estimates that it will have to spend an additional $26.2 billion.

This, says Feigenbaum, is where the insidious nature of the 28 by 28 projects comes into play. The budget-busting schedule is hard to justify, given the tenuous link between these projects and the Olympics.

"You basically have a list of projects that don't have anything to do for the Olympics, so the justification to pay extra to get them done early is pretty scant. It would be pretty challenging for the agency to manage these projects well," Feigenbaum tells Reason.

Often when governments want a project done quickly, they'll promise contractors and construction companies healthy bonuses to finish things by a target date. This isn't a bad practice per se, and it can be quite handy when expediting repairs or renovations of crucial infrastructure projects. (See, for instance, the bonuses that Georgia's Department of Transportation used as an incentive to rebuild a heavily trafficked Atlanta bridge destroyed by fire.) But paying out such bonuses for a project that isn't time-sensitive can leave Metro—and by extension taxpayers—spending much more than necessary. And doing it for multiple projects at the same time strains Metro's ability to manage the projects, making waste and abuse more likely.

On top of this, the additional $26 billion Metro has to spend to get these projects built in time all but necessitates a lot of new revenue sources. That's because all eight projects were passed as part of Measure M, a countywide ballot initiative that hiked sales taxes in order to pay for a long list of transportation goodies. Measure M binds Metro to a tight delivery schedule—and prohibits it from speeding up some projects by delaying or scaling back other Measure M projects.

That has left Metro scrambling to find new things to tax.

In December 2018 Metro CEO Paul Washington released a report which offered a number of such taxing possibilities, including new "mobility fees" on everything from ridesharing companies to electric scooters and bikes.

"These private companies are in the business of profiting from public investments in roads and infrastructure that enable their success," reads Metro's report, which goes on to say that new mobility fees could "can serve as the beginning of a more comprehensive regulatory plan."

Per-trip "mobility fees" ranging from 20 cents to $2.75 on ridesharing companies could generate anywhere from $25 to $552 million a year, Metro estimates. Slapping fees on dockless electric scooters could bring in another $58 million annually.

Another idea suggested by Metro is some form of congestion pricing. This is where drivers are charged a fee for the road space they take up that rises or falls depending on the level of traffic congestion. Depending on how it's implemented, the agency estimates that congestion pricing could raise anywhere from $1.2 billion to $10.3 billion a year.

Other suggestions floated by Metro include using public-private partnerships to help cut costs, and pursuing more state and federal transit dollars.

As a policy, congestion pricing is a pretty good way of reducing traffic congestion. Metro already operates several congestion-priced expressways in Los Angeles County, and international cities like London, Stockholm, and Singapore have successfully deployed it to cut down on congestion in their central business districts.

But in order to ensure it doesn't just become another tax, says Feigenbaum, the revenue generated from congestion pricing needs to spent on transportation improvements in the congested areas, which could include increased highway capacity or transit services along the congested routes where fees apply.

"When we want congestion pricing, we're doing it in order to solve the congestion, and improve mobility. Not just take that money and spend it on projects that are not necessarily connected," he says.

That's exactly what Metro is proposing to do when it suggests that congestion pricing could pay for transit improvements across L.A.'s sprawling urban area—including a number of dubious light rail projects that will do little to improve mobility or boost ridership.

Rather than spend a huge chunk of money building these new rail lines, or even expediting highway projects, Feigenbaum suggests that money could do a lot more to improve mobility, particularly for lower-income commuters, by just improving regular ole bus service.

This is actually a point that even fierce transit advocates have made.

Joe Linton of Streetsblog is far more supportive of light rail and critical of highways than Feigenbaum is, but he makes essentially the same point. "When Metro marshals its might to build shiny new capital projects, it sucks the remaining air out of the room. In turn, buses get older, less reliable, less frequent," writes Linton. "28 by 2028 should include system-wide all-door boarding, 28 new bus-only lane segments, more frequent buses—perhaps 28 more buses every day on 28 existing bus lines! Maybe 28 new bus lines! 28 more buses for municipal operators."

At the end of the day, Metro is using the Olympics to create a false sense of urgency behind projects that are going to happen anyway, and that have a tenuous connection at best to the Olympics. And to get them done in time for the games—a herculean, likely impossible task—it is willing to grab new tax dollars with both hands.

Comments