Jeb Bush's Plan to Regulate the Regulators

- OurStudio

- Sep 22, 2015

- 5 min read

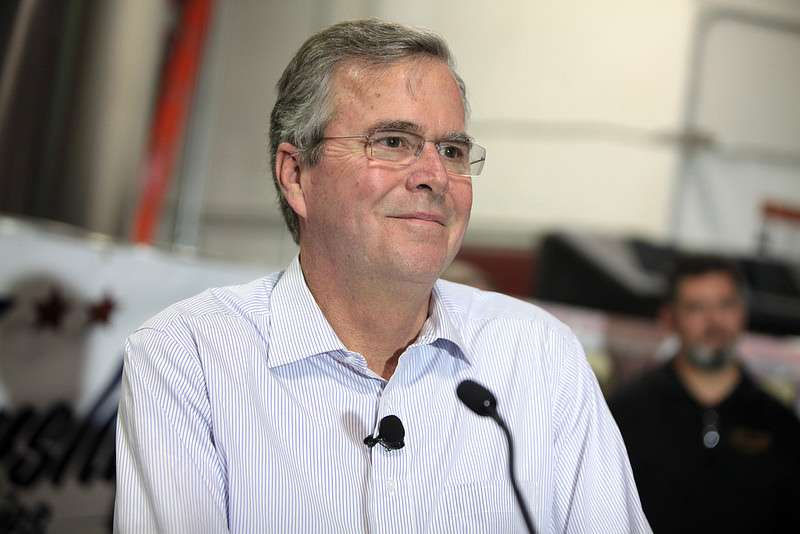

Gage Skidmore / Foter

Regulatory reform falls into the category of boring-but-important topics that should be a priority for any presidential candidate but rarely are. Boring, because it inevitably requires one to delve into wonky details of rulemaking processes in a slew of federal agencies that not man probably don't care about all that much, but important because of the massive, mostly unseen costs that regulation imposes on businesses and the economy: The total annual price tag for federal regulation is an estimated $1.9 trillion, and it effectively costs the average household about $15,000 a year.

Today, GOP presidential candidate Jeb Bush released a framework plan to streamline the federal regulatory process in order to mitigate at least some of that burden: According to a campaign document, Bush's proposal, in combination with his tax reform plan, would raise the income of a family of four earning $50,000 by about $3,100 annually, and increase GDP by about 3 percent over a decade. Estimating the cost of regulation—which in a lot of cases means trying to figure out what would have happened in the absence of certain rules is notoriously difficult to do with any precision, and campaign documents are likely to err toward suggesting a bigger impact, but still, that's a big enough effect that it'd be noticeable even the plan only got us half way there.

Bush's new policy paper, "The Regulatory Crisis in Washington," includes a lot of examples of regulation gone awry—everything from big stuff, like the two-tiered banking system that Dodd-Frank helped cement in place and the burdens the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau places to comparatively small ball, like Food and Drug Administration rules that effectively prohibit Americans from buying sunscreen that's safe and available all over the rest of the world. It also includes a variety of policy proposals, each of which falls into one of three broader goals: Scaling back existing regulation and promoting smarter regulation in the future, making regulators accountable to the public rather than to special interests, and reducing red tape in order to spur business dynamism.

The paper proposals a variety of mechanisms by which to achieve these goals. Among other things, it calls for a regulatory freeze "to the extent permissible under existing law" until approved by a newly nominated agency head; a regulatory "budget" to cap the cost of regulation during his first year in office, so that new regulations must be offset by cost reductions in existing rules; a "spring cleaning" to review rules in place and a retrospective review of new rules over an eight-year time-horizon; the nomination of judges who are less deferential to government agencies, along with legislation designed to limit agency power in the courts; a push to reform licensing regimes that protect incumbents; and a simplification of the permitting process to allow infrastructure projects to either be permitted or shut down within two years.

The goals are good, and the ideas are all worthy, or at least worth considering. Certainly, it's good to see that Bush is addressing the regulatory process in a serious and substantive way.

But ideas a lot like these have been floated and, on occasion, tried before. In 2011, for example, President Obama made a big show of calling for a significant regulatory review process aimed at eliminating onerous regulations in order to spur economic growth. It was useful as an acknowledgment that business regulation, in Obama's words, have resulted in "unreasonable burdens on business—burdens that have stifled innovation and have had a chilling effect on growth and jobs." But in the four years since the review was ordered, it hasn't really had much practical effect in terms of cutting back on regulation.

Indeed, in some cases it has just meant that hugely expensive regulatory moves are reframed as deregulatory measures. As Sam Batkins of the American Action Forum, a conservative think tank, noted last month, one Medicaid rule that added $3 billion in costs and nearly 2 million hours of paperwork was counted in one of the administration's regulatory reviews as a form of deregulation. All told, Batkins wrote, retrospective reports produced by the administration indicate that executive agencies have added about $14.7 billion in regulatory costs, plus more than 13 million hours of paperwork. This is not an effective way to cut back on rules and regulations.

Maybe that's just how the Obama administration works, and a future Jeb Bush administration would get it right. Bush's white paper certainly frames the regulatory crisis as a partisan issue, warning at the start of a "regulators-know-best mentality" that provides "the basis for President Obama's infamous and sometimes unconstitutional 'phone and pen' strategy to govern through regulation."

But the growth in regulation is an old and bipartisan problem. As Chris DeMuth of the American Enterprise Institute wrote in a compelling 2012 essay on the regulatory state for National Affairs, "The modern regulatory state is a bipartisan enterprise: During the half-century before President Obama's election, the greatest growth in regulation came under Presidents Richard Nixon and George W. Bush." Indeed, many major Obama-era regulations were primed by Bush-era legislation and rule changes.

Rather than a partisan or political issue, the growth of the regulatory state is, as DeMuth argues, an institutional issue—which is to say that it's a cultural issue, pervasive in Washington, in which it's become the norm for Congress to effectively hand over its legislative power to federal agencies. Instead of a Congress that makes law itself, we have a system of what DeMuth refers to as "delegated lawmaking," or "law-by-regulation," in which Congress provides regulators with goals and then essentially gives them carte blanche to institute whatever rules—which is to say whatever laws—they want in service of those goals.

All of this happens outside of the normal political process, and is in a real sense insulated from public oversight and the political pressures that go with it. Instead, DeMuth writes, we have a system of "regulatory administration [that] is cloistered and quotidian—characterized by piecework rulemaking, interest-group maneuvering, and impenetrable complexity." In addition to the financial burden, all this obscure interplay between regulators and lobbyists has the effect of reshaping a lot of corporate behavior, not stopping businesses from doing things so much as channeling their activities into forms more acceptable to the regulatory state.

Bush's proposals would, at best, only nibble around the edges of this deeper institutional problem—the problem of Washington's culture of unaccountable regulation. He would track it a little better, provide some sterner oversight, and try to force it to work within some limits. Basically, what he'd be trying to do is regulate the regulators, tweaking their practices through additional rules and systems designed to nudge them into better behavior.

It's worth trying, and it might produce some positive effects. But in the end, it probably wouldn't change the troublesome underlying dynamic in Washington. As regulators themselves often find out when they attempt to impose rules on businesses, it's hard enough to change a particular institutional practice—it's practically impossible to shift an entire institutional culture.

Comments