How Even Legal Marijuana Use Can Land You in Jail

- OurStudio

- Apr 16, 2019

- 5 min read

Last Tuesday, the New York City Council voted to stop testing probationers for marijuana use. The move is a reminder that even as states hammer out rules to legalize use—as New York is working through right now—remnants of the drug war have left a large population of Americans subject to the draconian measures of post-prison supervision.

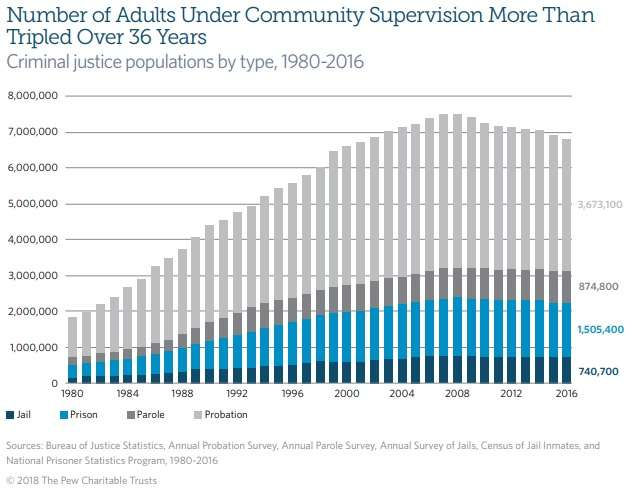

There are more than 4.5 million people on probation or parole in the U.S., nearly twice the number of people behind bars at any given time. All of these folks are subject to incarceration if they violate the terms of their supervised release, and in most places, a prohibition on using cannabis products may be one of those terms.

"Marijuana is a big issue when it comes to parole, but it's just the tip of the iceberg" explains Tyler Nims, the executive director of the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform. "Parole is a huge issue in criminal justice reform and in particular in New York. But it's unseen and unknown."

According to analysis of probation and parole figures put together by the Pew Charitable Trusts, a little more than half of probation and parole stints end without incident. But nearly 350,000 people get new jail terms annually because they've failed to complete probation or parole with a spotless record. In some states, revocation of supervised release is the main driver of incarceration. In Georgia, for example, 67 percent of new prison admissions in 2015 were due to revoked probation or parole. The same was true in Rhode Island, where 64 percent of new prison admissions in 2016 were due to supervised release revocations.

Judges have wide discretion to set the terms for release. That often includes prohibiting behavior that is otherwise perfectly legal. Probation and parole guidelines can limit where people go, who they can consort with, and what they may or may not consume. Earlier this year, a judge in Hawaii told a man arrested for stealing car that he could not consume Pepsi while on probation—and put him under supervised release for four years. While incidents like that one are relatively rare, prohibiting the use of marijuana while on supervised release is standard.

Whether marijuana use will continue to be deemed a violation is something to watch and weigh in on as state-level legalization continues.

Nims tells Reason that his organization started exploring parole reform as a way to close Rikers Island prison, shift the city toward smaller jails closer to the criminal courts across the boroughs, and reduce the city's overall jail population.

The good news is that incarceration in general is on the decline in cities across the country, including New York. But there's a big exception.

"Every category of person being detained has been decreasing except for those who are there for parole reasons," Nims says. He calculates that 40 percent of the city's parolees are re-incarcerated for non-criminal violations: things like failing drug tests and not living where they're ordered to live. Nims knew of a convicted sex offender who was given clearance by his parole officer to purchase a particular type of cell phone that didn't have internet access. It turned out the officer was wrong, and the offender was sent back to jail for a year for having the phone.

Parole and probation was not supposed to be this cruel, explains Vincent Schiraldi, a former New York City probation commissioner who is now co-director of Columbia University's Justice Lab. The prospect of getting out of prison earlier in exchange for being supervised was presented as an act of mercy or leniency. But as incarceration rates increased in lockstep with longer sentences, more people were put on parole and probation under increasingly strict terms. Supervised release changed from an act of mercy to a different form of punishment.

"As probation grew, you'd expect incarceration to decline," Schiraldi says. "It's much more logical to conclude that it's an add-on. It's just a net widener."

Schiraldi told a a New York Assembly committee in October that there's no public safety justification for routine marijuana testing of people on probation or parole. He testified that the research showed drug testing increased the likelihood of somebody ending back up in jail for technical violations, but did not actually reduce criminal behavior. In order to avoid testing positive, probationers and parolees instead avoid their mandatory meetings with supervisors, which causes yet another technical violation (known as absconding), which makes them even more likely to end up back in prison.

Schiraldi recommended to the Assembly that any law legalizing marijuana in New York should remove marijuana abstinence as a condition for parole or probation. When his office decided on to stop testing for marijuana, they were able to cut probation revocations nearly in half, and only four percent of their clients were convicted of a new felony within a year following the end of probation.

The push to end marijuana testing is part of a larger effort to reform and restore some of the mercy parole and probation were intended to provide and reduce the likelihood it ends with people being sent back to prison. In December 2018, a coalition of criminal justice reformers partnered with Assemblyman Walter Mosley (D-Brooklyn) to introduce the Less is More: Community Supervision Revocation Reform Act to try to make it less likely that technical violations of parole will lead to people getting sent back behind bars.

The Less Is More Act would eliminate incarceration for most technical violations, and for any exceptions would cap a return to prison to a maximum of 30 days. People under supervision will also be able to earn credits to reduce the amount of time they have to spend on parole. And when somebody on parole gets snagged for an alleged violation, they will be provided a hearing before they're detained (In New York City, somebody taken in for a parole violation can end up sitting at Rikers for 90 days before the state decides whether to send them back to prison). Several district attorneys, police chiefs, sheriffs, and many criminal justice reform organizations have signed on to support the bill.

A similar push is underway in Pennsylvania, where rapper Meek Mill has drawn attention to the arbitrary and harsh nature of how probation violations are handled. Mill faced two- to four-year prison sentence for a probation violation after he was filmed popping a wheelie on a dirt bike. He was eventually freed a year ago and used the experience to launch a justice reform group to change the way probation is handled. In early April, Meek's new group, the REFORM Alliance, put together a rally in Philadelphia to support probation reforms.

There was a bill introduced in Pennsylvania in January, SB 14, that would cap the length of probation to five years for felonies, three years for misdemeanors, and would also, like the Less Is More Act, limit the amount of time somebody can be incarcerated for technical (but not criminal) violations of probation.

Nims and Schiraldi both see these changes in parole and probation as vital reforms to our criminal justice system, up there with reforming bail systems that keep poor people trapped behind bars before they're ever convicted, and the elimination or reduction of mandatory minimum sentences that have handed down abnormally long prison terms for people convicted of certain types of drug crimes. Part of those reforms include making sure that as marijuana is legalized across the country, it doesn't remain a reason that people on parole or probation get sent back to prison.

"It's one of the least productive things you can do to for somebody coming back to the community," Nims says.

Check out the rest of our stories for Weed Week 2019.

Comments