Climate Change Prediction Fail?

- OurStudio

- Jun 17, 2016

- 6 min read

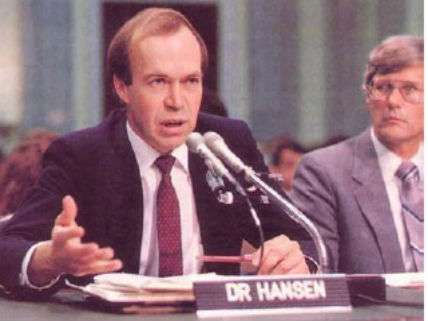

NASA

The Senate Environment and Public Works Committee held a hearing on June 10 and 11, 1986, to consider the problems of ozone depletion, the greenhouse effect, and climate change. The event featured testimony from numerous researchers who would go on to become major figures in the climate change debate. Among them was James Hansen, who was then a leading climate modeler with NASA's Goddard Institute of Space Studies and who has subsequently been hailed by the Worldwatch Institute as a "climate hero." When the Washington Post ran an article this week marking the 30th anniversary of those hearings, it found the old testimony "eerily familiar" to what climate scientists are saying today. As such, it behooves us to consider how well those 30-year-old predictions turned out.

At the time, the Associated Press reported that Hansen "predicted that global temperatures should be nearly 2 degrees higher in 20 years" and "said the average U.S. temperature has risen from 1 to 2 degrees since 1958 and is predicted to increase an additional 3 or 4 degrees sometime between 2010 and 2020." These increases would occur due to "an expected doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide by 2040." UPI reported that Hansen had said "temperatures in the United States in the next decade will range from 0.5 degrees Celsius to 2 degrees higher than they were in 1958." Citing the AP report, one skeptical analyst reckoned that Hansen's predictions were off by a factor of 10. Interpreting a different baseline from the news reports, I concluded that Hansen's predictions had in fact barely passed his low-end threshold. Comments from unconvinced readers about my analysis provoked me to find and re-read Hansen's 1986 testimony.

Combing through Hansen's actual testimony finds him pointing to a map showing "global warming in the 1990's as compared to 1958. The scale of warming is shown on the left-hand side. You can see that the warming in most of the United States is about 1/2 C degree to 1 C degree, the patched green color." Later in his testimony, Hansen noted that his institute's climate models projected that "in the region of the United States, the warming 30 years from now is about 1 1/2 degrees C, which is about 3 F." It is not clear from his testimony if the baseline year for the projected increase in temperature is 1958 or 1986, so we'll calculate both.

In Hansen's written testimony, submitted at the hearing, he outlined two scenarios. Scenario A featured rapid increases in both atmospheric greenhouse gases and warming; Scenario B involved declining emissions of greenhouse gas and slower warming. "The warming in Scenario A at most mid-latitude Northern Hemisphere land areas such as the United States is typically 0.5 to 1.0 degree C (1-3 F degrees) for the decade 1990-2000 and 1-2 degree C (2-4 F degrees) for the decade 2010-2020," he wrote.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) offers a handy Climate at a Glance calculator that allows us to figure out what various temperatures trends have been for the U.S. since 1901 and the globe since 1881. So first, what did happen to U.S. temperatures between 1958 and 1986? Inputting January 1958 to January 1986 using a 12-month time scale, the NOAA calculator reports that there was a trend of exactly 0.0 F degrees per decade for that period. Curiously, one finds a significant divergence in the temperature trends depending on at which half of the year one examines. The temperature trend over last half of each of the 28 years considered here is -0.13 F degree per decade. In contrast, the trend for the first half of each year yields an upward trend of +0.29 F degrees.

What happens when considering "global warming in the 1990's as compared to 1958"? Again, the first and second half-year trends are disparate. But using the 12-month time scale, the overall trend is +0.25 F degrees per decade, which would imply an increase of about 1 F degree during that period, or just over ½ C degree.

So what about warming 30 years after 1986—that is, warming up until now? If one interprets Hansen's testimony as implying a 1958 baseline, the trend has been +0.37 F degree per decade, yielding an increase of about 1.85 F degrees, or just over 1 C degree. This is near the low end of his projections. If the baseline is 1986, the increase per decade is +0.34 F degrees, yielding an overall increase of just over 1 F degree, or under 0.6 C degree. With four years left to go, this is way below his projection of a 1 to 2 C degrees warming for this decade.

Hansen pretty clearly believed that Scenario A was more likely than Scenario B. And in Scenario A, he predicted that "most mid-latitude Northern Hemisphere land areas such as the United States is typically 0.5 to 1.0 degree C (1-3 F degrees)." According to the NOAA calculator, average temperature in the contiguous U.S. increased between 1990 and 2000 by 1.05 F degree, or about 0.6 C degree.

Hansen's predictions go definitively off the rails when tracking the temperature trend for the contiguous U.S. between 2000 and 2016. Since 2000, according to the NOAA calculator, the average temperature trend has been downward at -0.06 F degree per decade. In other words, no matter what baseline year Hansen meant to use, his projections for temperatures in the U.S. for the second decade of this century are 1 to 3 F degrees too high (so far).

What did Hansen project for global temperatures? He did note that "the natural variability of the temperature in both real world and the model are sufficiently large that we can neither confirm nor refute the modeled greenhouse effect on the basis of current temperature trends." It therefore was impossible to discern a man-made global warming signal in the temperature data from 1958 to 1986. But he added that "by the 1990's the expected warming rises above the noise level. In fact, the model shows that in 20 years, the global warming should reach about 1 degree C, which would be the warmest the Earth has been in the last 100,000 years."

Did it? No. Between 1986 and 2006, according to the NOAA calculator, average global temperature increased at a rate of +0.19 C degree per decade, implying an overall increase of 0.38 C degrees. This is less half of Hansen's 1 C degree projection for that period. Taking the analysis all the way from 1986 to today, the NOAA calculator reports a global trend of +0.17 C degree per decade, yielding an overall increase of 0.51 C degree.

Hansen did offer some caveats with his projections. Among them: The 4.2 C degree climate sensitivity in his model could be off by a factor of 2; less solar irradiance and more volcanic activity could affect the trends; crucial climate mechanisms might be omitted or poorly simulated in the model. Climate sensitivity is conventionally defined as the amount of warming that would occur as the result of doubling atmospheric carbon dioxide. Three decades later, most researchers agree that Hansen set climate sensitivity way too high and thus predicted increases that were way too much. The extent to which his other caveats apply is still widely debated. For example, do climate models accurately reflect changes in the amount of cloudiness that have occurred over the past century?

The U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change's 1990 Assessment Report included a chapter on the "Detection of the Greenhouse Gas Effect in the Observations." It proposed that total warming of 1 C degree since the late 19th century might serve as a benchmark for when a firm signal of enhanced global warming had emerged. It also suggested that a further 0.5 C degree warming might be chosen as the threshold for detecting the enhanced greenhouse. According to the NOAA calculator, warming since 1880 has been increasing at a rate of +0.07 C degree per decade, implying an overall increase of just under 1 C degree as of this year. As noted above, global temperatures have increased by 0.51 C degree since 1986, so perhaps the man-made global warming signal has finally emerged. In fact, Hansen and colleagues suggest just that in a 2016 study.

The upshot: Both the United States and the Earth have warmed at considerably slower pace than Hansen predicted 30 years ago. If the three-decades-old predictions sound eerily familiar, it's because they've been updated. Here's hoping the new predictions will prove as accurate as the old ones.

Comments