Chicago Police Executed More Than 11,000 Search Warrants in Mostly Poor Neighborhoods Over 5-Year Pe

- OurStudio

- Jul 23, 2019

- 4 min read

New public records show Chicago police executed more than 11,000 search warrants over a five-year period, predominantly in the city's low-income and minority neighborhoods, and nearly half of them did not result in an arrest.

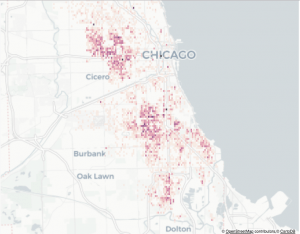

Data obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request filed by Lucy Parson Labs, a police accountability and transparency nonprofit in Chicago, shows that Chicago police executed 11,247 search warrants between 2012 and 2017, most of them heavily concentrated in the South and West Side of the city.

Distribution of executed search warrants by Chicago police, 2012-2017

"It looks very much looks like the stop-and-frisk data sets that we've released, very much like the asset forfeiture data we released," Lucy Parsons Labs director Freddy Martinez says. "It seems to match all of the enforcement patterns that we've seen over time by CPD, and follows the historical trend of where police are generating their activities, which is mostly poor neighborhoods."

The public records come just days after Chicago's Inspector General Joe Ferguson announced his office is investigating how Chicago police vet information and execute search warrants. The investigation was sparked by a string of lawsuits and a year-long series of stories by local news outlet CBS 2 that revealed a pattern of Chicago police executing busting into the wrong houses and terrorizing innocent families.

Sloppy, unverified search warrants led heavily armed Chicago police and SWAT officers to ransack houses; hold families, including children, at gunpoint; and handcuff an eight-year-old child in one case, CBS 2 found. In another case, 17 Chicago police officers burst into a family's house with their guns drawn during a 4-year-old's birthday party.

"Every one of these incidents is an aggravator and a perpetuator of mistrust that exists," Ferguson said announcing the inspector general investigation. "It really calls for a greater accountability and examination."

Chicago attorney Al Hofeld, Jr. has filed six lawsuits against the city on behalf of families who say there were wrongly subjected to violent, traumatizing police raids. In an interview with Reason, Hofeld called such raids a "silent epidemic that's being inflicted on a mass scale on kids in Chicago."

"Our work and CBS' work has uncovered the fact that these wrong, raids where they traumatize children, occur frequently in the city, and for decades it's been kind of an ugly fact that's been overlooked," he says.

In Hofeld's newest lawsuit, filed last week, a Chicago family claims police officers raided their house three times in four months looking for someone they say they don't even know.

Last June, Chicago settled a civil lawsuit by one family who claimed CPD officers stormed their house and pointed a gun at a three-year-old girl for $2.5 million. This June, two Chicago police officers were indicted on federal criminal charges alleging they paid off informants, lied to judges to secure search warrants, and stole cash and drugs from locations they raided.

Lucy Parsons Labs struggled for a year to get the data from the Chicago Police Department, which originally claimed the records did not exist.

The data shows just under 47 percent of the search warrants issued between 2012 and 2017 did not result in an arrest. However, a lack of an accompanying arrest is not necessarily an indicator of a botched raid. For example, the police may obtain warrants to search phones and other electronics. In nearly 800 of the search warrants, the address was listed on or near Homan Square, where the Chicago Police Department's Evidence and Recovered Property Section is located.

There are other curious spikes in the data, though. For example, Reason's analysis found that in most neighborhoods there were more search warrants that resulted in an arrest than did not. But in the Near West Side neighborhood, there were 160 search warrants executed over the five-year period that did not result in an arrest, compared to just 56 that did. The numbers don't explain the cause of that disparity, unfortunately.

"It's pretty hard to say one way or the other without access to more data," says Matt Chapman, an independent journalist and self-described "civic hacker" who helped Lucy Parsons Labs visualize the data. "We had to go to the state attorney general's office for a year to get this stuff. Unfortunately, we can't make a strong conclusion because we don't have as much info as we'd hoped, but we're hoping Chicago will release more information in response to our requests."

Chapman says, however, that the difference in the sheer number of search warrants was clear when he mapped the data onto a block grid of Chicago.

"The distribution is all in the South and West Side, whereas in the North Side most of the points didn't even get filled in," Chapman says. "Barely any search warrants happen on North Side. It's very clear that this is lopsided."

The data also show that search warrant executions declined from 2,278 in 2012 to 1,575 in 2017. That same year, the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division released a damning 164-page report that found Chicago police routinely used poor police tactics that resulted in unnecessary and unconstitutional force, including against minors.

Reason has been reporting on the scourge of wrong-door SWAT raids for more than a decade. Radley Balko wrote in 2006 about the frequency and tragic outcomes of botched raids. They are often the result of poor information and a failure to do basic vetting, like checking to see if the subject of a search warrant still lives at the address. But they're also a consequence of the militarization of police. The use of SWAT teams rose from around 3,000 deployments per year in 1980 to as high as 80,000 a year currently.

Chicago is not alone. In 2016, New York City's Civilian Complaint Review Board reviewed hundreds of cases and found scores of illegal or botched home searches by NYPD officers.

In response to a request for comment, the Chicago Police Department said it was prohibited from commenting due to the pending inspector general investigation.

Comments