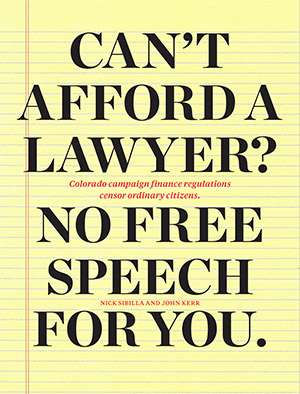

Can't Afford a Lawyer? No Free Speech for You.

- OurStudio

- Dec 19, 2016

- 9 min read

Reason

For someone campaigning to help run Colorado's university system, Matt Arnold didn't seem too keen on higher education. His 2012 Republican primary campaign for a spot on the Board of Regents made headlines after the candidate admitted that he had misstated finishing his master's thesis, maligned those who received degrees for their "pursuit of academic BS that no one cares about" by calling them "a bunch of people who hang letters after their names, but they have no useful skills," and then publicized his opponent's home address. In the heat of the controversy, a group called Coloradans for a Better Future (CBF) ran an ad criticizing Arnold's campaign as "an embarrassing distraction." This, it seems, was the moment that Arnold's mission changed from winning political office to an anti-speech vendetta.

Proving the old adage that academic politics are so vicious because the stakes are so low, Arnold began an all-out legal attack on his detractors. Appearing on a local radio show in 2014, he threw down the gauntlet: CBF's supporters, he said, "need to be dragged into court" and "exposed for the cowardly, backstabbing scum that they are."

Arnold and his newly founded Campaign Integrity Watchdog group proceeded to file complaint after complaint against CBF. At one point, he even demanded that the state disbar CBF's attorneys.

The relentless litigation paid off. In 2014, an insolvent CBF filed a "termination report" with the Colorado Secretary of State. But that only prompted Arnold's fourth complaint. He now claims that a lawyer had helped CBF file for termination and that the lawyer's pro bono aid amounted to a political "contribution" that should have been reported.

As in many states, political participants in Colorado are subject to strict caps on contributions. State legislature candidates can receive no more than $400 per donor during an election cycle. Political committees—politically engaged citizens who have banded together into a group—can accept only $575.

But campaign finance attorneys regularly charge hundreds of dollars per hour for their services. So an organization that received as little as one billable hour in pro bono or reduced-cost legal aid would quickly blow through the state's contribution limit. Citizens with few resources would be utterly defenseless against litigious opponents.

As far back as 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court held that pro bono representation is a "fundamental" right that merits protection under the First Amendment. Regulations cannot "abridge unnecessarily the associational freedom of nonprofit organizations" that offer legal assistance, the high court ruled in In re Primus. The only other court to consider this issue—in Washington state—ruled that regulating free legal assistance as a contribution is "unconstitutional."

Despite these clear precedents, the Colorado Court of Appeals sided with Arnold, ruling in April that free or discounted legal aid can be regulated and restricted as a "contribution."

In August, the Institute for Justice, the public interest law firm where we work, petitioned to overturn that decision. "The Court of Appeals' ruling meant that Coloradans could find themselves breaking the campaign finance laws simply by working with a lawyer to try to comply with those laws," says Paul Sherman, a senior attorney at I.J. "That sort of Catch-22 is unjust and unconstitutional."

Thankfully, the Colorado Supreme Court has agreed to review the case. It also stayed the lower court's ruling. What happens next will not only have significant ramifications for free expression, it will also shine a light on Colorado's peculiar system for regulating political discourse, which at every turn favors censorship over free speech. Coloradans who wish to exercise their First Amendment rights are uniquely exposed, thanks to the state's system of private-party enforcement. In 2002, Coloradans voted in favor of Amendment 27, which enshrined a package of ambitious campaign finance regulations into the Colorado Constitution. But enforcing those laws was outsourced to the public at large.

Under the state constitution, "any person" who suspects someone may have violated Colorado campaign finance law can file a complaint with the secretary of state. Within three days, the secretary must forward the case to the Office of Administrative Courts, triggering full-blown litigation, where parties can subpoena and depose each other. Since those cases proceed in civil court, defendants do not have a right to a free attorney. Cases are ultimately heard by an administrative law judge, who determines liability and can impose sanctions. Appeals can last for years.

Incredibly, the victims of baseless complaints have little recourse to recover their court costs. Like in other civil cases, any prevailing party is supposed to be entitled to recover their attorney's fees. But there's a catch. Although campaign-finance violations are heard by administrative law judges, they do not have the power to enforce their awards for attorney's fees. Instead, that can only be done in state district court.

Colorado explicitly only allows the secretary of state or the complainant to file a motion to enforce such an award—not respondents. In other words, even if someone targeted by a complaint prevails in court, they cannot recover their legal fees. As recently as May 2016, the Colorado Court of Appeals ruled that state law "leaves a respondent awarded fees and costs without a remedy…to enforce that award." That asymmetry practically invites the thin-skinned to game the system.

In most states, publicly accountable officials would promptly review such complaints, serving as a filter for baseless or litigious claims. Not in Colorado. Regardless of the complaint's motivation or merit, the secretary of state "shall refer the complaint to an administrative law judge," with no discretion allowed.

Consider a 2010 case that began when a candidate for the Colorado House scrawled a handwritten complaint claiming he was "constantly being harassed by e-mail and Facobock mossges [sic]." He asked the court to subpoena AOL for his critic's contact information and then began filling the court record with MySpace stories about bondage parties, which he claimed his online tormenter had authored. It took an administrative hearing and over two months in the judicial system before the case was dismissed.

Although Amendment 27 was heavily pushed by progressive groups, including Common Cause, the League of Women Voters, and the Colorado Public Interest Research Group, the crowd issuing the complaints is bipartisan. The Colorado Republican Committee once filed a complaint against a Democratic candidate for the state House; the executive director of the Colorado AFL-CIO sued the Colorado Right-to-Work Committee, resulting in nearly $10,000 in fines levied against the latter.

Last year, a school was sued for sharing a Facebook post about one of its students' mothers. The complainant was the campaign manager for the mother's political rival.

In another case, the leaders of a recall campaign against three GOP county commissioners in Elbert County were subjected to months of litigation (prosecuted by the Elbert County Republican Party), based solely on the county clerk's failure to properly process the paperwork required to register the group as an "issue committee." In almost any other state, a simple phone call would resolve that sort of problem.

Arnold, the Board of Regents candidate, is responsible for more campaign finance complaints in Colorado than anyone else. Out of the more than 340 complaints that have been filed since Amendment 27 passed 14 years ago, more than 50 were filed by him or his Campaign Integrity Watchdog group. As Arnold once explained, the campaign finance system is a tool for waging "political guerrilla legal warfare (a.k.a. Lawfare)" against one's opponents.

Earlier this year, The Colorado Independent revealed a "pretty sweet deal" Arnold offered the Colorado Republican Committee after he sued them. The cases would go away if the committee paid Arnold $10,000 and shut down one of its political committees. But if didn't pay up, Arnold wrote, "'the beatings will continue until morale improves' ;-)." After the Independent published its story, Arnold threatened to subpoena the reporter who covered the case. Other lawsuits have bordered on the absurd. In January, Arnold filed a complaint demanding the state impose a $36,000 fine because two $3 contributions weren't properly reported. Later that month, Arnold sought over $10,000 in penalties against a first-time school board candidate who failed to register a candidate committee. But the candidate properly registered in October, two hours after he learned he made a mistake, and months before Arnold sued him. No wonder an administrative law judge once admonished Arnold for filing claims that were "nothing more than a game of 'Gotcha.'"

Proponents of campaign finance regulations cite the need to combat "dark money." Amendment 27 was passed explicitly in part to curb the perceived power and influence of "wealthy individuals, corporations, and special interest groups." But the sheer pettiness of so many complaints reveals that, in fact, the law invites intimidation and reprisals against those who try to exercise their First Amendment rights. The resulting burden falls hardest on the very people that campaign finance laws purport to protect: ordinary citizens, grassroots activists, and small groups.

One of those people is Tammy Holland, a small-town mom living in Strasburg, Colorado, about 40 miles east of Denver. In 2015 Holland objected to the Common Core curriculum in her son's public school and even pulled him out in protest. Holland also began taking out ads in her local newspaper slamming standardized testing and Common Core. Two months before an upcoming school board election, Holland placed two ads identifying all eight candidates on the ballot and noted that some of the incumbents "no longer have children" in the district—but, crucially, the ads did not advocate for or against any specific person.

Officials gave her civics project a failing grade. In September 2015, Superintendent Tom Turrell filed a campaign finance complaint against Holland, on behalf of himself and the school district. The action accused Holland of violating state law by failing to register as a political committee and not including a "paid by" disclaimer in the newspaper advertisements.

Holland was shocked. "I never would have imagined that in America I could be sued simply for putting an ad in my local newspaper," she says. "I had never even heard of campaign finance. I never had a second thought that it had anything to do with me."

Facing a legal hearing, and with no way to evaluate the validity of Turrell's claims by herself, Holland was forced to hire an attorney. Then, two days before the scheduled court date, the superintendent dropped his complaint.

But when Holland tried to recover her legal costs, board president Tom Thompson warned her at a public board meeting that she'd better keep her lawyer. Days later, he filed a campaign finance lawsuit of his own, making the same meritless assertions that his colleague, Superintendent Turrell, had just withdrawn.

It took almost six months for an administrative law judge to rule that Thompson had "failed to establish any of the violations alleged."

Holland's victory should not mask the serious constitutional violations she had to overcome and continues to face. Government officials targeted her based on her political views and demanded she "apologize" for speaking her mind. The complaint was dismissed only with the help of pro bono legal aid, a right now jeopardized by the Colorado Court of Appeals' decision that such assistance counts as a campaign contribution.

The Institute for Justice filed a federal lawsuit on her behalf in January 2016. Since Colorado's abuse-prone enforcement scheme is set in the state constitution, only a victory in federal court (or a new constitutional amendment) can end it. In the meantime, Holland has stopped running newspaper ads. Who can blame her?

Colorado is just one example of a troubling nationwide trend. In Alabama, registered lobbyists (which include those who handle legislative affairs at nonprofits) must complete an ethics course, in person, before they are allowed to make even a single phone call to elected officials. The course is only offered in Montgomery, just four times a year.

Until recently, a Minnesota law dished out First Amendment rights on a first-come, first-served basis: Under the state's "special sources" limit, the first few people who donated to a candidate were able to donate twice as much as subsequent donors. Fortunately, after a federal judge ruled that the limit would "constitute a penalty for the 'robust exercise' of [a person's] First Amendment rights," state legislators repealed the law in 2015.

One of the most dramatic abuses saw SWAT-team tactics deployed against political speech in Wisconsin. To investigate whether a group of activists had "coordinated" speech about public affairs with Gov. Scott Walker's campaign in 2012, a state district attorney authorized what the Wisconsin Supreme Court would later call "paramilitary-style home invasions." As the court described it, "search warrants were executed…in pre-dawn, armed, paramilitary-style raids in which bright floodlights were used to illuminate the targets' homes." It took more than two years for a majority of the state Supreme Court to put an end to the investigations.

Unsurprisingly, complying with campaign finance regulations can be extremely onerous. Analyzing the complexity of campaign finance red tape, I.J. and Jeffrey Milyo, an economist at the University of Missouri, in 2007 asked more than 200 regular citizens to complete disclosure forms common to grassroots political activity. "No one completed the forms correctly," the report found. "In the real world, all 255 participants could be subject to legal penalties including fines and litigation." One participant even said the experience was "worse than the IRS!"

Laws that dissuade people like Tammy Holland and groups like Coloradans for a Better Future from expressing their opinions corrode the foundations of public discourse. Campaign finance regulations don't create a thriving marketplace of ideas. They silence the citizens who have the fewest resources.

Comments