Obamacare vs. the Current Flawed System

- OurStudio

- Oct 15, 2012

- 5 min read

New York Times' columnist Nicholas Kristof tells the story of a college pal named Scott Androes who has Stage 4 prostate cancer and would have been better off, says Kristof, had Obamacare been around a decade or so sooner. "If you favor gutting 'Obamacare,'" writes Kristof, "please listen to Scott's story."

But what follows is no easy-peasy parable of universal coverage uber alles. It's equal parts wilfully stupid decisions on the part of Androes and—this is no small thing—health care costs being driven up by precisely the sort of regulations and bureaucracy that Obamacare will put on a heavy dose of steroids. Far from proving anything about the need and urgency of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, it simply shows that even individuals with the means to pay for coverage and the sort of education that ostensibly creates responsible adults (the story endlessly rehashes the irrelevant fact that Kristof and Androes are Harvard grads) sometimes make awful, even tragic, choices.

At the end of 2003, Androes, a bachelor in his 40s, says he went through a "midlife crisis" and quit his job as a pension consultant. He writes that he "didn't buy health insurance because I knew it would be really expensive in the individual policy market." He later found part-time work (which didn't offer benefits) doing tax returns for H&R Block and by 2011 he "began having greater difficulty peeing. I didn't go see the doctor because that would have been several hundred dollars out of pocket — just enough disincentive to get me to make a bad decision."

It wasn't an infection, as Androes and the urgent-care doctor he eventually saw thought at first. It was cancer that had advanced very far. Androes is being treated as a charity case in a Seattle hospital:

The bill is already north of $550,000. Based on the low income on my tax return they knocked it down to $1,339. Swedish Medical Center has treated me better than I ever deserved.

For Kristof, the moral of all this is clear: "It would have made more sense to provide Scott with insurance and regular physicals. Catching the cancer early might have saved hundreds of thousands of dollars in radiation and chemo expenses — and maybe a life as well." And, of course, Mitt Romney is an uncaring proponent of a health care system that is "repugnant economically as well as morally."

However, the article, which includes Androes' reflections as well as Kristof's more pointed commentary, doesn't really come close to supporting such a conclusion. Kristof notes that Androes "could have afforded insurance, and while working in the pension industry he became expert on actuarial statistics; he knew precisely what risks he was taking." In choosing to remain uninsured while able to afford coverage, Androes is hardly alone. In 2006, for instance, about 43 percent of uninsured Americans were in households making more than 2.5 times the poverty line.

Androes himself writes:

Why didn't I get physicals? Why didn't I get P.S.A. tests? Why didn't I get examined when I started having trouble urinating? Partly because of the traditional male delinquency about seeing doctors. I had no regular family doctor; typical bachelor guy behavior. I had plenty of warning signs.

So maybe if he'd been forced to buy insurance against his will, he would have also visited the doctor for annual physicals including prostate exams or at least blood screens for that sort of trouble.

Maybe, though having insurance and using it for the sorts of regular care (such as blood screens for PSA levels) that would have caught this problem early on are very different matters. Although Kristof quotes studies that conclude close to 30,000 people a year die prematurely due to a lack of health insurance, the link between having health insurance and having improved health is far from clear. When it comes to prostate and colon cancers, studies of Medicaid patients in Florida and elsewhere show that despite having insurance, covered patients actually fare worse than uncovered patients who are equally poor.

So having insurance is hardly the be-all and end-all that many supporters of a universal mandate presume. That's even more the case when you factor in the likely outcome that an increase in the number of patients without a corresponding increase in the number of providers will hardly make it easier for people to schedule routine examinations. Add to that the lack of strong correlation between what Obamacare critic John Goodman says is "the amount of health care inputs and the overall health of a population." Other studies show that relatively low life expectancies in the U.S. are due to lifestyle choices (smoking, diet, and the like) and accidents (especially driving ones) rather than access to health care. And even taking that into consideration, studies show that not having health insurance and not having health care are not the same thing (the uninsured consume about 40 percent of the amount of health care as similarly aged insured indivduals).

Kristof says that Mitt Romney would consign folks like his friend to death with nary a second thought. That's not quite right, either, and it shows how quickly health care debates get reframed in partisan terms. As governor of Massachusetts, of course, Romney pushed his signature reform which is the very model of Obamacare. Had Androes lived in the Bay State rather than Washington, he would have at least been paying for insurance whether he wanted to or not around 2007 or 2008. And for all his bluster about repealing Obamacare, Romney has already said that if he becomes president, he's happy to keep various aspects of the law, including the ban on denying care due to preexisting conditions.

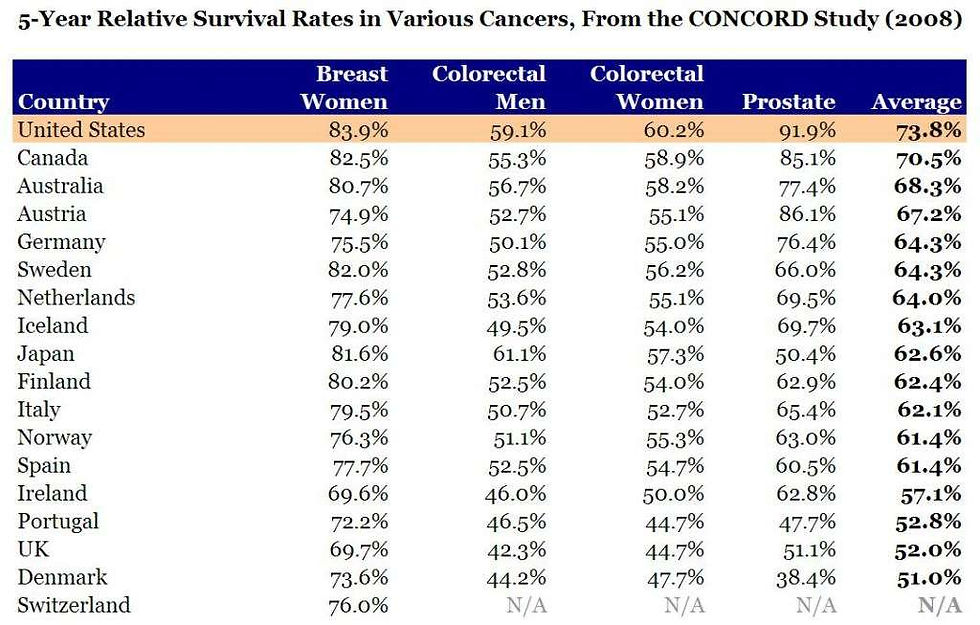

The story Kristof tells is not a happy one, to be sure. If Androes had acted differently, his cancer might have been caught much sooner when it was more easily treated. Certainly, that would have cost less both in terms of heartache and anxiety and in terms of dollars and cents. But the fact is also that Androes is getting treatment—and in a way that is not bankrupting him. And if you have deadly cancer, you're better off on average to be in the United States than anywhere else in the developed world; the five-year survival rates for most cancers are better here than in Canada, Europe, or Japan.

What's missing from Kristof's piece—and from too much of the discussion about health care reform—is any sense of how the current employer-based system (which Obamacare does virtually nothing to change) came into being and how an actual market in the provision of health care (not even insurance per se) might improve the situation. Why do blood tests and basic checkups cost so much? It's not because markets are allowed to work; indeed, it's precisely because every aspect of the delivery system is wrapped up in more red tape than we can imagine or untangle. By adding more bureaucracy and oversight from afar, Obamacare will certainly increase many of the problems it set out to address. And there's no reason to believe that the law—whose cost estimates are already climbing prior to full implementaiton—will make care cheaper or better. It might make insurance universal (in name anyway), but that is hardly the point of either Kristof's story or any real reform (for that, read this 2009 piece by Reason Science Correspondent Ronald Bailey as a starting point).

Comments